Issues & Priorities in Competency-

Based Education

CBE is by definition more complex than our current time-based system. What issues and priorities do we need to grapple with now, and what are the design implications for the future?

The move to competency-based learning models raises serious practical and philosophical questions. This section discusses some of the major issues influencing the CBE landscape and the implications for the design choices ahead.

The Paradox of Competence

Reductionists vs Constructivists

Since Ted Sizer’s Coalition of Essential Schools (formed in 1984), there have been networks of “show what you know schools” that, consistent with a constructivist approach, value project-based learning (PBL) and periodic public exhibitions of learning. Now often referred to as deeper learning networks as a result of Hewlett Foundation grants, school networks including New Tech Network, EL Education, Big Picture Learning, High Tech High, and Asia Society rely on cohort progressions out of tradition and equity-based intentions to maximize the benefits of peer learning.

At the other end of the spectrum are examples of online credit-recovery opportunities for students who have failed high school courses. Adaptive and diagnostic assessments quickly identify learning levels and gaps. Students move through asynchronous curriculum as rapidly as possible, taking end-of-unit multiple-choice tests to demonstrate mastery. While designed to be useful for getting over-aged and under-credited students back on track, credit recovery programs typically have low-skill development benefits.

In this report we attempt to embrace the benefits and represent the learnings of these two camps — authentic high-agency student work resulting in public products and rigorous and scalable systems; individual, team, and cohort learning experiences; and extended deep dives and accelerated progress.

Closing Gaps with a Focus on Equity

CBE provides a great opportunity for gap-closing equity. However, as Achieve notes, “Without attention paid to risks to equity, competency-based pathways could have negligible effects on persistent disparities in performance among students by race/ethnicity, income, special education, and ELL status. Far worse, it also could open up new achievement gaps — ones not based on different levels of performance but on the time it takes to reach standards if different groups are moving at disproportionally slower paces through the content.”16

It is imperative that significant efforts are made to pay attention to the risks and plan for CBE that closes, rather than exacerbates, gaps.

The CompetencyWorks report Quality and Equity by Design offers a comprehensive framework for how equity can be woven into a CBE system. The principles are represented in the image below, and reflection questions for generating conversation can be found in the report.

EQUITY PRINCIPLES

In order to seek educational equity, district and schools will…

Nurture Strong Culture of Learning and Inclusivity

Support Students in Building Skills for Agency

Establish Transparency About Learning, Progress, and Pace

Engage Community in Shaping New Definitions of Success and Graduation Outcomes

Develop Shared Pedagogical Philosophy Based on Learning Sciences

Ensure Consistency of Expectations and Understanding Proficiency

Monitor and Respond to Student Progress, Proficiency, and Pace

Invest in Adult Mindsets, Knowledge, and Skills

Respond and Adapt to Students Using Continuous Improvement Processes

Image source: Adapted from Quality and Equity by Design: Charting the Course For the Next Phase of Competency-Based Education, iNACOL.

In April 2018, CompetencyWorks and iNACOL released the report, Designing for Equity: Leveraging Competency-Based Education to Ensure All Students Succeed which unpacks each of the principles referenced in the above graphic. Each principle is followed by key characteristics, a rationale that explains why the principle is important for equity, suggested policies and practices guide further exploration, “look for” and red flags which provide examples of effective or problematic practices to trigger capacity building, and reflection questions that serve to launch discussion.17

The Lumina Foundation has also provided guidance on how CBE can be used to help solve inequalities at the post-secondary level in the report “How Competency-Based Education May Help Reduce Our Nation’s Toughest Inequities.” Stephanie Malia Krauss of Jobs for the Future, the author of the report, recommends three priority learners that CBE should focus on: 1) underserved learners of color, 2) unemployed and underemployed adults, and 3) adults with some college, but no credential. From there, she outlines the priority programs that would best serve the needs of these individuals: 1) certificate and degree programs, 2) new forms of credentials, 3) general education courses, and 4) college access and success programming.

Jobs for the Future provides good guidance on how to potentially overcome equity pitfalls in their Students at the Center report, “Equity in Competency Education: Realizing the Potential, Overcoming the Obstacles.” There are six potential learning inequities in CBE that the authors address, along with ways to possibly mitigate them: 1) metacognitive learning strategies, 2) self-regulation and perseverance, 3) technological access and use in schools, 4) technological access and use in homes, 5) technological use by individuals, and 6) access to learning content and learning experiences.

If competency-based systems are designed with equity in mind, they should yield an increase in the percentage of K-12 students that graduate ready to succeed in post-secondary learning and work. They will have verified skills with evidence of achievement.

The primary risk of competency-based education is poorly defined goals, resulting in students rushing through a checklist of objectives or skills without mastering core concepts and complex skills or applying their learning to new contexts. What we measure matters.

Why is Competency-Based So Hard?

Six specific challenges include:

Defining competencies:

a narrow checklist is reductionistic, broad competencies are hard to verify

Transition challenges:

transforming a system is a technical, pedagogical, cultural challenge

Tools and resources:

platforms and materials focus on age cohorts, they aren’t built for individual progress

Technical challenges:

limited interoperability makes it hard to combine data

Reporting:

grading and reporting student progress, building common mastery transcripts, aggregating system level success measures are all new challenges

Accountability:

old systems (higher education, transcripts, NCAA) still rely on seat time and grade levels

Common Barriers to Competency-Based Education

Thus far, we have offered a definition, provided a rationale, and surfaced key issues and ideas. Before exploring design choices and learning tools for CBE, we believe it will be helpful to surface current barriers and inherent gaps. Expert interviews and research have identified six thematic areas with barriers to progress outlined below.

1. Defining competencies

It is challenging to define competencies that are clear and signal important priorities without being reductive and inadequate.

Lack of well-defined competencies.

The development of Common Core State Standards was a step toward shared student learning goals in core subjects, but there are still thousands of objectives without aligned assessments.

Lack of equity as a priority.

Nick Donohue, President and CEO of Nellie Mae Education Foundation (NMEF), has sponsored much of the remarkable policy progress in New England. When asked why there wasn’t more progress in New England high schools, he said it was a lack of well-defined goals — there was not a sense of urgency, particularly about accelerating the progress of previously underserved students. Donohue thinks breakthrough progress will be made when we face structural racism more directly and honestly.

Lack of definition of work-ready skills.

There is growing interest in social and emotional learning, much of which NGLC calls habits of success, but no shared definitions or measures. Aspen Institute’s National Commission will make some progress on this front in 2018.

2. Transition challenges

All of the issues associated with moving from the transition from tracking time to demonstrating learning are complex. The inertia of the old system — and everyone’s experience with it — is challenging to overcome.

Difficult transitions to standards-based grading.

Replacing traditional letter grades with standards-based rubrics and requiring mastery rather than just accumulating points are key changes in practice and communication.

Moving from a culture of success vs. failure to a culture of revision.

Rather than a failing grade, competency-based schools tell students they have not yet achieved mastery. They create more time and support for more learning. When work doesn’t meet standards, they ask students to revise it. Competency-based schools often engage community members to help provide feedback.

Adoption of new roles and development of new capabilities for all teachers.

One of the biggest issues to tackle, and one of the best levers, is building professional capacity amongst teachers, virtually all of whom have grown up in and were trained through a traditional, age-based model.

Limited supports.

For struggling students to stay on track, they need real-time academic and social supports. Equitable competency-based education requires more time, innovative teaching, and learning strategies and support for students that need help; and that takes weighted funding (i.e., school budgets that reflect the challenges that enrolled students bring to school) and flexible funding.

Inadequate teacher preparation and professional learning.

Some teacher preparation programs have begun to incorporate personalized learning, but few are strong on competency-based learning progressions. Because competency-based learning models remain idiosyncratic, generic preparation is of limited value (i.e., more preparation needs to be model specific).

Pressure to retain privilege.

Parents of students who have been successful within the current system often view school’s “job to be done” as preparation for selective universities; and anything that appears to erode this priority — such as abandoning honors classes, traditional grading, and class rank — is fiercely opposed.

3. Tools and resources

Learning platforms and gradebooks for tracking mastery are inadequate. There are few instructional resources with aligned assessments.

Few platforms support dynamic learning.

Most learning management systems are built for whole group instruction to age cohorts. They lack the content management, assessment, mastery tracking, and dynamic scheduling needed to manage a CBE environment.

Few quality curriculum materials.

While there are more instructional materials that claim to be standards-aligned, there are few designed specifically to support competency-based learning progressions and learning outside of age bands. Much of mastery-focused curriculum is currently home-grown. This is one of the areas where many people interviewed for this report stated a challenge. It is surprising how few options there are and how little progress that has been made to date.

4. Technical challenges

The range of systems, data, and infrastructure used with CBE leads to numerous technical challenges to be addressed.

Lack of a common student record.

Each state will need to define a common electronic student record. More broadly, a learner profile will be relatively fluid, with lots of opportunities to customize.

Limited interoperability.

There are issues around access, transfer, and security of data. It is very difficult to combine formative feedback from different sources. In addition to being a psychometric and technical problem, this is a business model challenge — most traditional vendors make money selling item-level data and don’t want to share it.

Inability to combine formative assessment from multiple sources.

5. Reporting

Post-secondary reporting for college entrance and legislative demands on grouping students are a challenge to full implementation of CBE. Challenges include:

Higher education reliance on traditional measures.

Universities still rely heavily on standardized test results, grade point averages, and course-taking patterns as signals of likely post-secondary success.

No common competency transcripts.

For universities to begin recognizing competency-based transcripts, there will need to be a common format with the ability to verify skill assertions.

NCAA still pushes seat time.

David Haglund, Pleasanton Unified School District superintendent, said, “The biggest barriers are at the high school level and relate to NCAA and the university entrance requirements. The NCAA, for example, still wants to see gradebooks and syllabi that show the number of days and/or hours of seat time and a teacher grade” (see this iNACOL webinar for more).

6. Accountability

Current accountability systems are a challenge for CBE.

Accountability systems reinforce grade levels.

Federal accountability legislation provides more flexibility for competency education but still reinforces grade-level grouping and testing.

The biggest barrier may be that there are so few comprehensive, highly effective competency-based learning models.

Design Choices for Competency-Based Education

The move to competency-based learning models raises serious practical and philosophical questions. This section discusses some of the major issues influencing the CBE landscape and the implications for the design choices ahead.

Personalized and competency-based learning involves intentional design choices about experiences and environments that stand in contrast to traditional education on many fronts.

These design choices come under the broader context of school design. As Carnegie Corporation’s Opportunity by Design implored, “We must seize this opportunity to redesign schools to enable personalized learning. This means fundamentally reshaping the use of human capacity, technology, time, and money, to provide both recuperative and accelerative opportunities for all students.”21

The 10 principles of a high-performing secondary school outlined in Opportunity by Design include several principles that directly point to a competency-based approach; for example, prioritizing mastery, empowering and supporting students, and personalizing learning.

For purposes of this report, it is useful to identify three categories of overarching design choices that schools must make related to a competency-based approach: targets and competencies, learning processes, and grading processes.

Targets & competencies

FIELD OF LEARNING

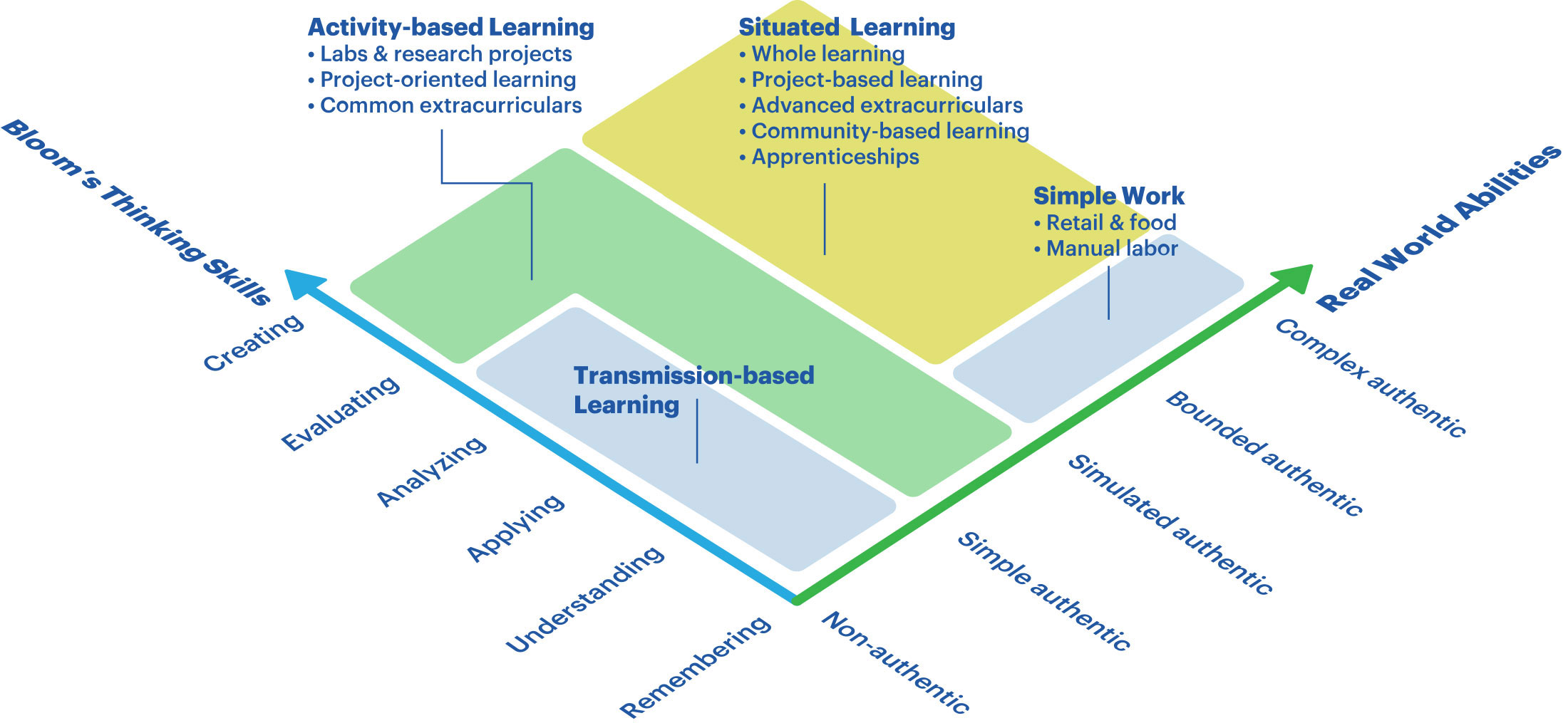

The broader, deeper learning experience matches higher order thinking with more authentic practice

Image source: Adapted from Visual Summary of the MyWays Student Success Series. NGLC.

The author of the math standards, Jason Zimba, proposed a wiring diagram that reflects sub-skill clusters and relationships. Jen Medbery, founder, and CEO of Kickboard said it may be necessary to keep the sets of subskills distinct and allow gradebook users to build rules that group sub-skills.23 Districts and networks could choose from a couple of different credentialing or badging schemes linked to skill clusters. See also The Art and Science of Designing Competencies by curator Chris Sturgis.

If simply tracking a checklist of skills won’t cut it, solutions will need to include micro-standard tagging grouped into skill clusters — a two- or three-layer hierarchy supporting the ability to combine fine grain and broader performance assessments. As Medbery said, a couple of different options and the ability to customize would be helpful.

To boost student engagement and simplify stakeholder reporting, the solutions should be, as Michael Fullan suggests, “irresistibly engaging” for students and “elegantly efficient” for teachers.24 Students should be able to log into a mobile application and quickly understand what they need to learn and options for demonstrating mastery. Teachers should be able to efficiently monitor progress, benefit from informed recommendations and dynamic scheduling, and pinpoint assistance for struggling students.

NGLC’s MyWays competencies aim to address the tension outlined by Fullan as they require an integration of thinking skills and real-world abilities. NGLC posed the question, “How do we create learning experiences that foster new social skills, the tolerance of ambiguity, entrepreneurism, or the ability to identify opportunities?” The Field of Learning map represents a traditional student experience heavy with transmission-based instruction with some labs and research projects focused on higher-order thinking skills, a smattering of more authentic extracurricular activities, and maybe some after-school work.

Work in traditional schools is along the left axis separate from the real and more complex settings that would promote durable and transferable learning. Dynamic competency-based models value situated (or place-based) learning whereas higher-order thinking skills are engaged within real-world settings that are either bounded (within a controlled setting) or complex (unbounded).

It may go without saying that knowledge and skill maps will vary depending on where the approach lands on the constructivist-reductionist spectrum.

Learning process

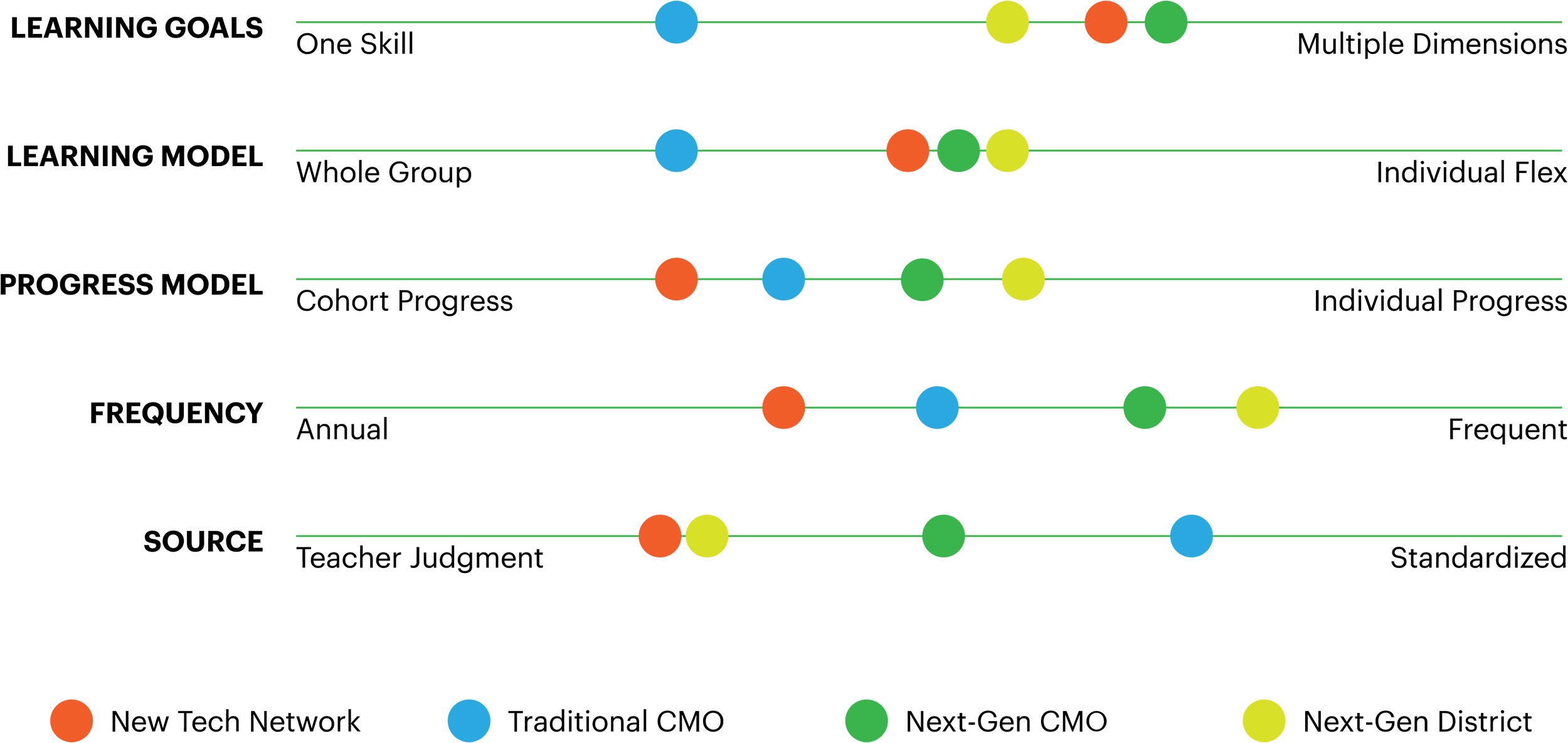

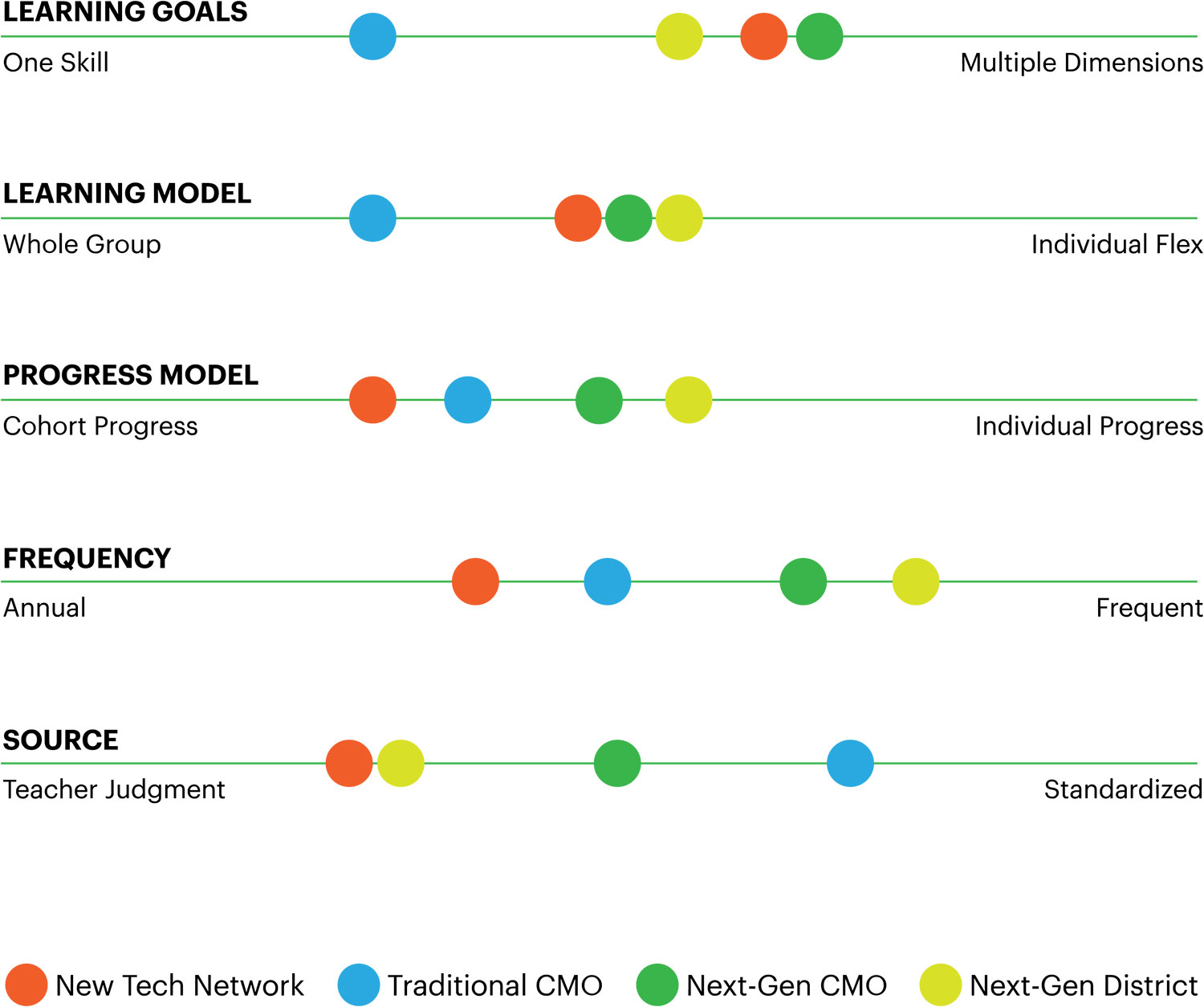

• New Tech Network is representative of the 10 Deeper Learning networks sponsored by the Hewlett Foundation (and also those supported by other organizations)

• Next-generation CMOs (such as Brooklyn LAB and Thrive) adopted broader aims, incorporating more PBL and sophisticated personalization strategies.

In the following chart, each of the five design choices is shown as a continuum with the four school types arrayed along it. Clearly, there are substantial differences, even among these leading schools and school models (it is worth noting that this graphic is intended primarily for visualization, and does not reflect all members of each grouping).

LEARNING PROCESS DESIGN CHOICES

Learning goals:

Learning model:

Progress model:

Frequency of assessment:

Source:

STANDARDS-BASED GRADING

After designing learning targets and experiences, the type of feedback students receives may be the most important set of design decisions. Standards-based grading involves numerous design and implementation choices — all potential barriers to progress.

“When there are any negative reactions [to districts advancing competency education], they are in response to new grading practices, usually referred to as standards-based grading,” observed Chris Sturgis, CompetencyWorks co-founder.25

Problems arise “when districts use grading as the entry point (which puts all the focus on the grading and not on why competency education is valuable) or they’ve put some of the pieces of standards-based grading in place but not the entire framework necessary to make it more trustworthy than traditional grading,” added Sturgis. Brooklyn Lab Charter School experienced the difficulty of leading with grading during the school’s first year of operation. Co-founder Erin Mote stated, “We epically failed in our first year by rolling out a competency-based report card without talking to parents, and they were incredibly frustrated and even angry about the change — some were vocal about it. We called an all-school town hall the next week to both explain and to provide a traditional report card alongside a more competency-based one.”26

Because grading and progress reporting is student- and parent-facing, they are the most externally visible design components. They change the form of the answer to the question every parent asks: “How is my son/daughter doing?” When the answer is a bunch of numbers associated with a set of standards rather than letter grades by subject, parents are often confused by and may question, the new system.

The chart below shows the difference between traditional and standards-based grading.

To avoid parent and teacher revolt when implementing standards-based grading, districts and networks must make the case for change: quality preparation, personalized learning, equity, and learner agency. Implementation should feel intuitive for students and parents and well supported for teachers; if it’s confusing and technically challenging, it won’t be well received.

Schools using standards-based grading and competency-based progressions should have a set of agreements about the use of formative assessment: some items simply inform learning; others are combined into mastery judgments using a weighting system, trailing average, or just the most recent item.

In practice, schools that claim to be competency-based showed little difference in assessment practices, according to a Nellie Mae-sponsored comparison with traditional schools. The 10 competency-based schools in this comparison did, however:27

- Have higher clarity on learning targets,

- Use learning plans and technology to personalize learning,

- Give students who need it more time and support, and

- Provide opportunities for students to make some of their own decisions about learning.

Rather than being an accurate comparison of CBE and traditional schools, the survey indicates the fuzziness of early implementation and a lack of clarity about language and practices on the basics like grading.

Some districts make the distinction between competency-based grading and standards-based grading, suggesting that the former is more about the application of organizing principles and meeting students where they are.

Traditional Grading

- Based on assessments (quizzes, tests, homework). One grade per assessment.

- Assessments based on percentages, criteria may be unclear.

- Include every score regardless of when collected, then average the record.

Standards-Based Grading

- Based on learning goals and performance standards. One grade per learning goal.

- Standards are criteria for proficiency and provided ahead of time.

- Emphasize the most recent evidence of learning.

Sign up for our newsletter

Get the latest educator insights and practical classroom tips every other week, direct from the XQ community

Follow us to #RethinkHighSchool