Metacognition in the Classroom and Beyond

As a teacher, one of my favorite activities was having students share strategies for solving the…

As a teacher, one of my favorite activities was having students share strategies for solving the same math problem. Students always came up with different ways to answer even the most basic questions, and it was great for me to see how their minds worked.

The best part of this activity was the discussion that it prompted. Students would debate how and why different strategies worked well and whether they agreed with them or not. Every student encountered a new way of thinking beyond their own.

On a typical day, high schoolers are asked to master a set of complex academic skills and concepts. As teachers, it’s our job to ensure they have the tools to do so. Teaching students how to use flashcards to memorize new vocabulary or how to create an outline before writing an extended essay helps students think through new ideas and approaches.

But just as flashcards or outlines can help students learn new content, activities like sharing strategies for solving a math problems, help students develop their metacognitive skills.

What is Metacognition?

From Socrates to John Dewey, the idea of self-reflection has long been a cornerstone of learning. But the term “metacognition” first appeared in the 1970s through the work of developmental psychologist John Flavell.

Metacognition is the mental process of understanding what and how one thinks, and so metacognitive skills are the capabilities that allow a person to analyze their thought process, how it’s constructed, as well as what strategies can be employed to strengthen it.

Flavell wrote: “Metacognition refers to one’s knowledge concerning one’s cognitive processes or anything related to them.” While most students are taught how to think through concepts, metacognition focuses on taking a pause in the thinking process, to better understand how someone got to where they are.

Researcher Linda Darling-Hammond and her team identified two important aspects of metacognition. The first is reflection—thinking about what we know. The second is self-regulation—the ability to manage how we go about learning. Both these skills are vital in creating lasting learning experiences and developing lifelong learners.

For students, having metacognitive skills allows them to recognize new approaches to learning. These skills help them gain a deeper understanding of themselves—including their own strengths and weaknesses—in order to accurately evaluate their performance, understand the causes of their successes or failures, and formulate a plan to make changes.

How Does Metacognition Work?

Most adults practice metacognitive skills every day, often unaware they are even doing so. Maybe you’re about to give a speech. You know in the past you’ve had a tendency to speak too fast, so before starting you remind yourself to take a deep breath between sentences and to take pauses by looking up at your audience. But for teens, that ability to self-reflect doesn’t come naturally and needs to be modeled and taught.

Some fundamental questions teachers can use to teach and develop metacognitive thinking in teens include:

- What are my learning goals?

- How am I going to learn this?

- How will I double-check that I have it right?

- How does this new content fit in with what I already know?

- How well do I know this?

- Can I apply this new knowledge or skill in other subject areas or situations?

Imagine two students learning how to find volume and surface area in geometry. A student with developed metacognition abilities will recognize if they are having trouble and think about the math problems they have previously solved. They will think about strategies they used then and if any could work for their current challenge. They will try different strategies until one works, and if they continue to struggle, typically they will ask for help.

On the other hand, a student lacking metacognitive skills might struggle with their homework assignments, quizzes, and tests. They won’t always know if they’re using the right formula or making calculation errors. They may hesitate to ask questions or ask for help because they probably don’t recognize what they don’t know.

Why is Metacognition Beneficial for Students?

Research from the Center for Innovative Education and Prevention shows that explicit instruction in metacognition can lead to positive learning, regardless of subject or grade level. As Donna Wilson and Marcus Conyers explained, metacognition “supports learning by enabling us to actively think about which cognitive strategies can help achieve learning, how we should apply those strategies, how we can review our progress, and whether we need to adjust our thinking.”

Metacognition is linked to better academic performance and improved critical thinking skills. It can also help teens in a number of other areas, including reading comprehension and problem-solving skills. Metacognition promotes self-directed learning, which helps students communicate their knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Increasing student metacognition skills supports the development of soft skills, which include competencies like creativity, collaboration, and conflict resolution. At XQ, we’ve identified many of these soft skills in our XQ Learner Outcomes—a series of learning outcomes, like being a generous collaborator and becoming an original thinker, that aim to prepare students for a changing future. Our research-backed Learner Outcomes position students to engage deeply with their learning, building their creativity, critical thinking, independence, and agency.

Possessing these soft skills is important for success in the classroom and the real world. Having a solid awareness of how to think about your thinking helps teens and young adults beyond graduation. If we want students to be equipped to reflect on questions like what makes them happy, how they live a good life, and how they discover a fulfilling career, they need support in understanding how to think about their decisions, the relationships they make, and how they think about their goals.

Above all, developing strong metacognitive skills can help students find balance as they enter the adult world.

How Do I Teach Metacognitive Skills in My Classroom?

According to developmental psychologist Ann L. Brown, metacognitive thinkers know how to recognize flaws or gaps in their thinking, articulate their thought processes, and revise their efforts.

However, many of these skills are not innate in students and require targeted instruction. Because of traditional schooling models, some students grow accustomed to parents and teachers over-monitoring their academic progress. Students need to make mistakes and learn how to correct those errors. With metacognition, they can deliberately pause in those moments of errors and explicitly name the process that helped them solve their discrepancies.

Research shows children as young as three are capable of developing fundamental forms of metacognition. By high school, students are ready to tackle the challenge of more abstract thinking and how to take true ownership of their learning. Because these skills are ubiquitous, all teachers have an opportunity to reinforce metacognitive practices to support students broadly.

Strategies to improve metacognition in students

At XQ schools and partnerships, making students active participants in the classroom begins with meaningful, engaged learning opportunities. When you plan lessons where students work with their peers, engage deeply with content, and have the chance to ask dynamic questions, it becomes that much easier to incorporate opportunities for honing metacognitive skills.

For example, teachers can pair activities with a “productive struggle.” A productive struggle is a metacognitive strategy where students approach a problem through various means, learning how their thinking led them to a solution. Oftentimes, students reach a dead end and then have to reevaluate their thinking up to that point.

Activities like the productive struggle encourage students to use mistakes as a catalyst for improving their learning, because students learn more when correcting minor mistakes than when no errors are made. Productive struggles and correcting mistakes also promotes a growth mindset in your classroom, which in turn helps to build resiliency and persistence in students. Realizing that mistakes are a natural part of the learning process, students learn to grow through hard work and determination.

It’s also important to foster students’ inquiry and curiosity. While some students might be willing to ask questions in front of their classmates, others might be too shy or self-conscious about the questions they have. Or they might not even know how to formulate the questions they need to ask. Quick, low-stakes strategies like exit tickets, One-Minute Papers, or even knowledge checks can help boost learning.

Whether you are using the productive struggle, or inquiry-based models, below are some other activities to help boost the metacognitive strategies students use in your classroom.

Use Thinking Journals

Thinking or learning journals are an easy way for students to reflect on how rather than what they learn, according to developmental psychologist Marilyn Price-Mitchell. Many English teachers use reading journals to support student comprehension, and this follows the same format. Rather than focusing on a text, students focus on themselves, utilizing reflective thinking by asking questions like:

- What was easiest for me to learn this week? Why?

- What was most challenging for me to learn? Why?

- What study strategies worked well as I prepared for my exam?

- What strategies for exam preparation didn’t work well? What will I do differently next time?

- What study habits worked best for me? How?

- What study habits will I try or improve upon next week?

To reinforce active learning, have students ask these questions to each other, recording their thoughts down once they’ve listened to one another. Next, ask students to share what they’ve heard with others. Encourage them to find patterns and common threads.

Focus Your Discussions

In her book “The Independent Learner,” author and educator Nina Parrish shows that class discussion can break out of the pattern of teachers asking questions with students providing answers. Instead, metacognitive talk can be an instructional tool where students ask questions, debate ideas, and develop more complex thinking and reasoning skills.

To encourage metacognitive talk, teachers should limit their own talking and turn the mic over to students. Use open-ended questions and encourage students to use multiple strategies in order to problem-solve. In a STEM class, students can work on a mathematical problem that was solved incorrectly. Have students openly discuss how the errors were made and the potential solutions. This can encourage students to compare and contrast different ways of thinking, building a more dynamic understanding of their peers.

KWL charts

KWL charts are graphic organizers that students use before, during, and after a unit or lesson to keep track of what they know about a topic (K), what they want to know (W), and what they learned (L). This activity guides students to use background knowledge, develop a purpose for their learning, and reflect on their knowledge. Throughout the unit or lesson, students can go back and check off questions they’ve answered, come up with new questions, and make note of any misconceptions they had in the beginning.

Have Students Teach Students

In a reciprocal teaching activity, students become the instructor by working in small groups to teach specific skills to their peers. One common structure involves each student taking on a specific role—summarizing, asking questions, clarifying, and making predictions—to see how each component of critical thinking looks. Once students have a grasp of each strategy, they then take turns leading discussions and guiding their peers to mastery.

This strategy is very effective when scaffolding and differentiating instruction. Students learn well from one another through collaboration, and reciprocal teaching opens the door for more metacognitive teaching strategies. Reciprocal models work well in labs, small group projects, and reading circles.

Plan Feedback Sessions

Peer feedback is a collaborative process that encourages students to think and read critically by learning how to provide constructive criticism. Feedback is a crucial step for growth because it allows students to identify and correct mistakes they have made. However, learning how to give feedback is just as beneficial as receiving feedback. As described above, learning to identify mistakes and offer helpful suggestions to their classmates boosts learning more than if there were no errors made.

Put Metacognition Into Practice

High school is busy, but it’s important to make time for students to pause and think about their thinking. Providing opportunities to ask questions, reflect on their strengths and weaknesses, and work together to problem-solve are great ways to hone metacognitive skills that will stay with your students long after graduation.

Check out these other great resources for inspiration to bring metacognition into your classroom:

Ideas for teaching metacognition skills from the Brookings Institution

Four Research-Based Strategies All Teachers Should Use from The Cult of Pedagogy

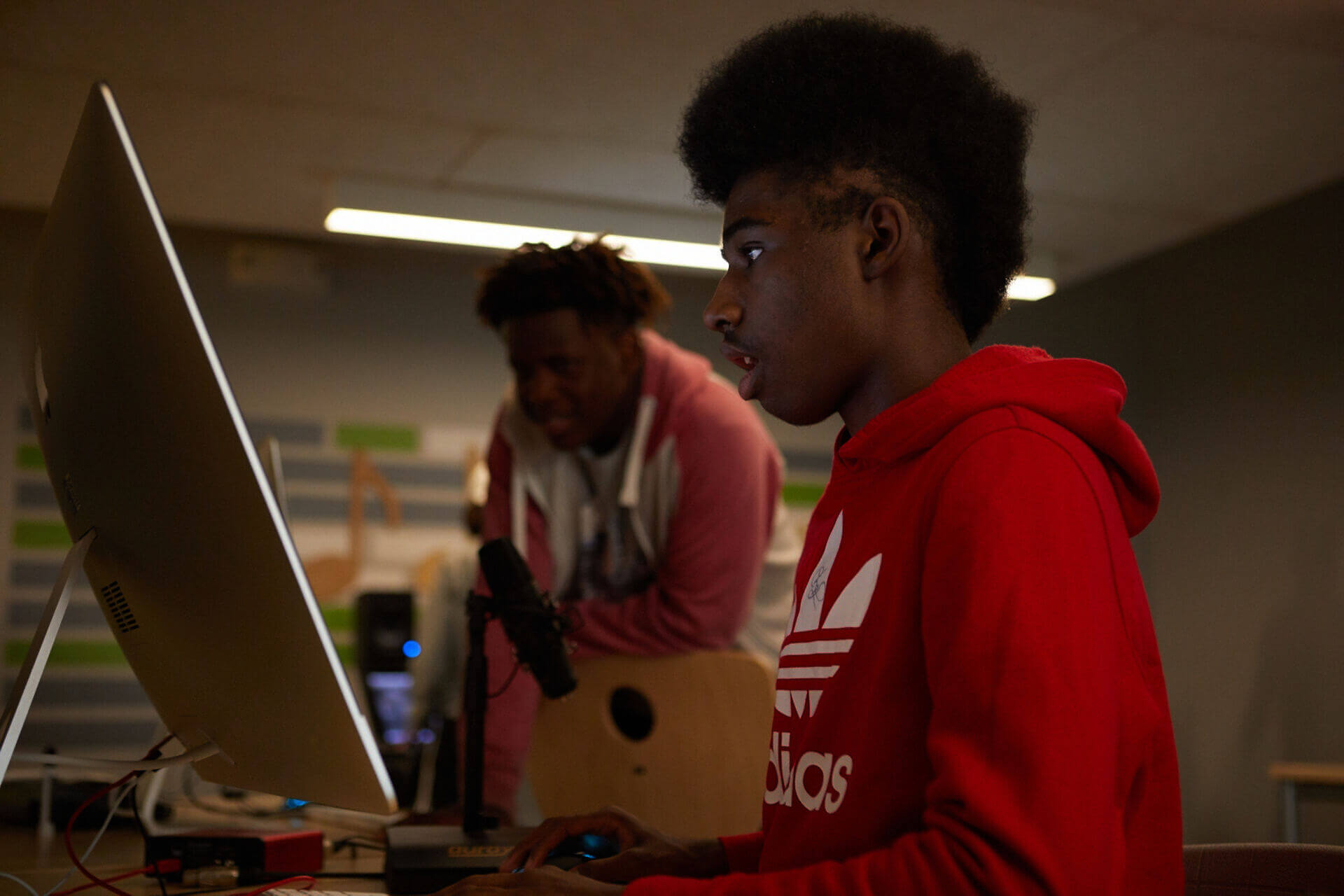

Photo at top by Maya Richardson