Translate Momentum

Into Action

In this section, we'll provide concrete ideas for how you can:

- Empower Local Communities

- Make Diplomas Meaningful

- Get Teachers the Tools They Need

Once you’ve galvanized people in your state around the need for change and given them some images of what’s possible, you’ll be prepared for action. That means enacting policies and taking other steps to give communities, educators, students, and families the building blocks to achieve the state’s vision for transforming high schools and preparing all students for the future of work.

- Empower Local Communities

Just as no two students are the same, no two communities are the same. So why should our high schools be? Real progress occurs when local communities are empowered to design their own solutions to the common challenge of ensuring that all students—regardless of background—graduate prepared for success after high school.

As a state leader, you can encourage local design teams to take advantage of each community’s unique assets while drawing inspiration from research-based design principles and the best examples of what’s possible. You can unleash local creativity within a framework that emphasizes statewide priorities for high school transformation and offers increased flexibility in return for greater transparency and accountability.

Communities are eager to take on high school redesign. When XQ invited communities across the country to engage in a design challenge, more than 10,000 people from all 50 states, representing nearly 4,000 communities, answered XQ’s call to propose student-centered designs for 21st-century learning—a stunning response far greater than we anticipated. The XQ national challenge took teams through a process grounded in design thinking that flipped traditional school reform on its head.

Teams started out in a phase called DISCOVER, during which they studied what students need to know and be able to do to succeed in the future of work, learned about advances in adolescent learning, and listened to the aspirations and experiences of students and teachers. They moved on to DESIGN, during which they drafted bold, original school designs that would truly meet the needs of students. Only then did they move on to DEVELOP, during which each team delved into the practical challenges of enacting its design.

By reversing the order of pragmatism and brainstorming, the XQ challenge freed teams to create highly original school designs—designs that break down barriers that have for too long stifled progress toward developing the modern high schools we need. XQ’s school design resources, Knowledge Modules, and lessons learned can provide state leaders and local community members with a sound starting point so that they don’t have to reinvent the wheel.

Here are three specific suggestions for getting new ideas flowing in communities across your state:

- Offer incentives to design schools of the future

- Create an "innovation" status for traditional schools

- Use pilot programs to seed innovation

Find XQ Knowledge Modules at:

https://xqsuperschool.org / schools /

VIRGINIA: OFFERING GRANTS TO INCENTIVIZE HIGH SCHOOL REDESIGN

Virginia has awarded high school innovation planning grants in the past several years to local school districts that submitted competitive proposals to rethink how high schools prepare students for college and careers, including through “student-centered learning, with progress based on student, demonstrated proficiency” and “‘real-world’ connections that promote alignment with community workforce needs.” Applicants identify potential policy impediments as a step to obtaining streamlined access to necessary waivers. By the end of 2017, 11 districts had successfully applied for planning grants, and four of those had also been awarded second-year implementation grants.16

THE ROAD TO REIMAGINING HIGH SCHOOL.

ANNOUNCE A

CHALLENGE

Make it ambitious, inspiring, and different. XQ called on education inventors, students, teachers, parents, business people, youth workers, artists, entrepreneurs, and everyone in between to ask themselves what high school could be.

MOVE PEOPLE

TO ACTION

HELP TEAMS

DREAM SMART

Put equity, innovation, and excellence at the center of it. XQ created a plethora of free resources to help the teams. Our 13 XQ Knowledge Modules offer a mix of cutting-edge academic research and inspiration.

VISUALIZE THE

PROCESS

Map out the steps and a timeline so people can see how to get involved and where the work will lead them. XQ created a three-phase process that turned conventional school planning on its head:

Discover

Explore the Landscape:

Begin by listening to young people, studying the latest science on brain development and how people learn, and understanding the community a school will serve.

Design

Create a school where mission and culture, teaching and learning, student engagement, and community partnerships come together in an audacious, original design.

Develop

Produce a plan that considers all the realities involved in launching a school, from staffing and budget to innovative uses of time, space, and technology.

MEET PEOPLE

WHERE THEY ARE

Spread the word about rethinking high school far and wide. XQ advertised the competition on billboards, TV, radio, and social media. We drove the XQ Super School Bus to communities around the country, listening to students and bringing people together.

Assemble a diverse group of well-respected people to narrow down the applicants. XQ used a comprehensive rubric to help 44 judges select the most promising designs. Judges were a diverse group, spanning the political, technology, and education spectrum.

REWARD THE

BOLD ONES

Choose designs that change people’s thinking about high school. XQ selected teams that listened to students, involved the community, emphasized equity, and challenged the status quo.

NO WINNERS

OR LOSERS

Honor everyone who gives their time, energy, and effort to redesigning high schools. XQ continues to be out on the road, listening to people and inspiring communities. To date, the XQ Super School Bus has visited 66 cities in 32 states and held 76 student roundtables.

MORE SCHOOLS,

MORE ENGAGEMENT

Months after announcing the first 10 Super Schools, XQ found that many unchosen teams had continued working, even without the award. Some had progressed and improved on their ideas, inspiring us so much we made more grants to honor their persistence.

XQ SUPER

SCHOOLS

Today, the XQ Super School Cohort is a network of 19 schools on their journey toward becoming Super Schools. Together these schools are a beacon for the nation, shining a light on a brighter future for all students.

Nearly every state has enacted a charter school law that allows significant room for innovative school designs. However, only about a dozen states have established a process that allows traditional districts and schools to obtain the same kind of broad flexibility for ambitious innovation based on an approved design. Schools need to have the ability to allocate their budgets, make staffing decisions, and use time in different ways to implement innovative programs.

Beyond providing flexibility, state innovation policies can raise awareness about new possibilities and inspire local community members to take action. For example, Powderhouse Studios, an XQ-supported school that is seeking approval to operate under an innovation school plan in Somerville, Massachusetts, got its start when the mayor of Somerville approached a local youth and community-education program about launching a new high school under the state’s innovation initiative. Innovation policies vary from state to state. While states such as Massachusetts allow for innovation schools based on an approved school-level plan, other states such as North Dakota allow whole districts to apply for innovation status. States can also allow districts to establish “innovation zones”—networks of semi-autonomous schools, such as Denver’s Luminary Learning Network, that operate under considerable policy flexibility and a unique governance structure. Some states, such as Tennessee, use innovation zones as an improvement strategy for so-called turnaround schools that have been identified as chronically underperforming through state accountability systems. Innovation zones—with accountability for reaching performance targets—can offer a strategic approach to redesigning education in high schools identified for improvement under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), including a category of high schools with low graduation rates.

ESSA provides funding for states and districts to support targeted school improvement efforts. It also provides block grant funding that can be used to implement many aspects of high school redesign, such as providing students with a well-rounded education that includes a wide range of coursework, community-based learning, technology-driven innovations, Advanced Placement (AP), and International Baccalaureate (IB) courses and exams, dual enrollment courses, and teacher training to personalize student learning.

State leaders must ensure that flexibility is coupled with responsible oversight and accountability. For example, Colorado’s innovation policy requires the state to publish detailed annual reports about the progress of innovation schools collectively and each school individually on an annual basis. Massachusetts requires local superintendents to evaluate innovation schools annually, including progress on goals for improving student achievement outlined in approved plans.

Massachusetts launched its Innovation Schools initiative in 2010. Under the initiative, local communities can create in-district schools with the autonomy to implement innovative designs to improve student achievement and reduce achievement gaps. The policy provides broad flexibility in key areas—curriculum, budget, school schedule and calendar, staffing, professional development, and local district policies—while offering a streamlined process to obtain supplemental waivers of state policy as necessary. In exchange, local districts hold innovation schools responsible for meeting progress in achieving measurable annual goals set out in their plans. Communities across the state have established more than 50 innovation schools over the past eight years, nearly half of the secondary or high schools.

States can use pilot programs to cultivate and test out specific new approaches to high school education, such as competency-based learning, across a group of school districts. Through pilot programs, states can support local innovation on a smaller scale while analyzing the process of turning ideas into action. Pilots can identify common challenges, successful strategies, and conditions for success across differing communities.

In order to maximize the impact of pilots, states should create mechanisms for sharing lessons learned by developing professional learning communities across program participants. It is also essential that these programs include mechanisms for assessing whether students are acquiring the knowledge and skills necessary for success post-graduation.

For example, Illinois recently launched a Competency-Based High School Graduation Requirements Pilot through which more than a dozen school districts are exploring new ways for high school students to learn and earn credits for high school graduation. The districts are creating approaches that allow students to earn credits at their own pace by demonstrating mastery of essential content and skills.

Under the Illinois pilot, students can advance as soon as they demonstrate mastery, but they can also spend additional time—and receive personalized support—if they need it. Students must be able to earn credit toward graduation requirements in ways other than traditional coursework, including learning opportunities outside the traditional classroom setting. And they must have opportunities to earn advanced postsecondary credits and career-related credentials.

The Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design (DSISD) launched as Denver’s first competency-based high school under a state-approved “innovation plan” in 2015. Created in partnership with the school district’s innovation lab, the Imaginarium, the school’s focus on innovation and design thinking is central to a student experience that is personalized and competency-based. DSISD is designed around four competencies of innovators, and mastery of these competencies is integrated into all course work. Starting in ninth grade with a class called “Design My Future,” and continuing every year, students engage in sequenced activities that propel them to take on more and more ownership of their learning. Opportunities to take college classes begin in ninth grade. By 11th grade, every student pursues an extended internship. And by senior year, students can earn early college credit for all or most of their coursework.

- Make Diplomas Meaningful

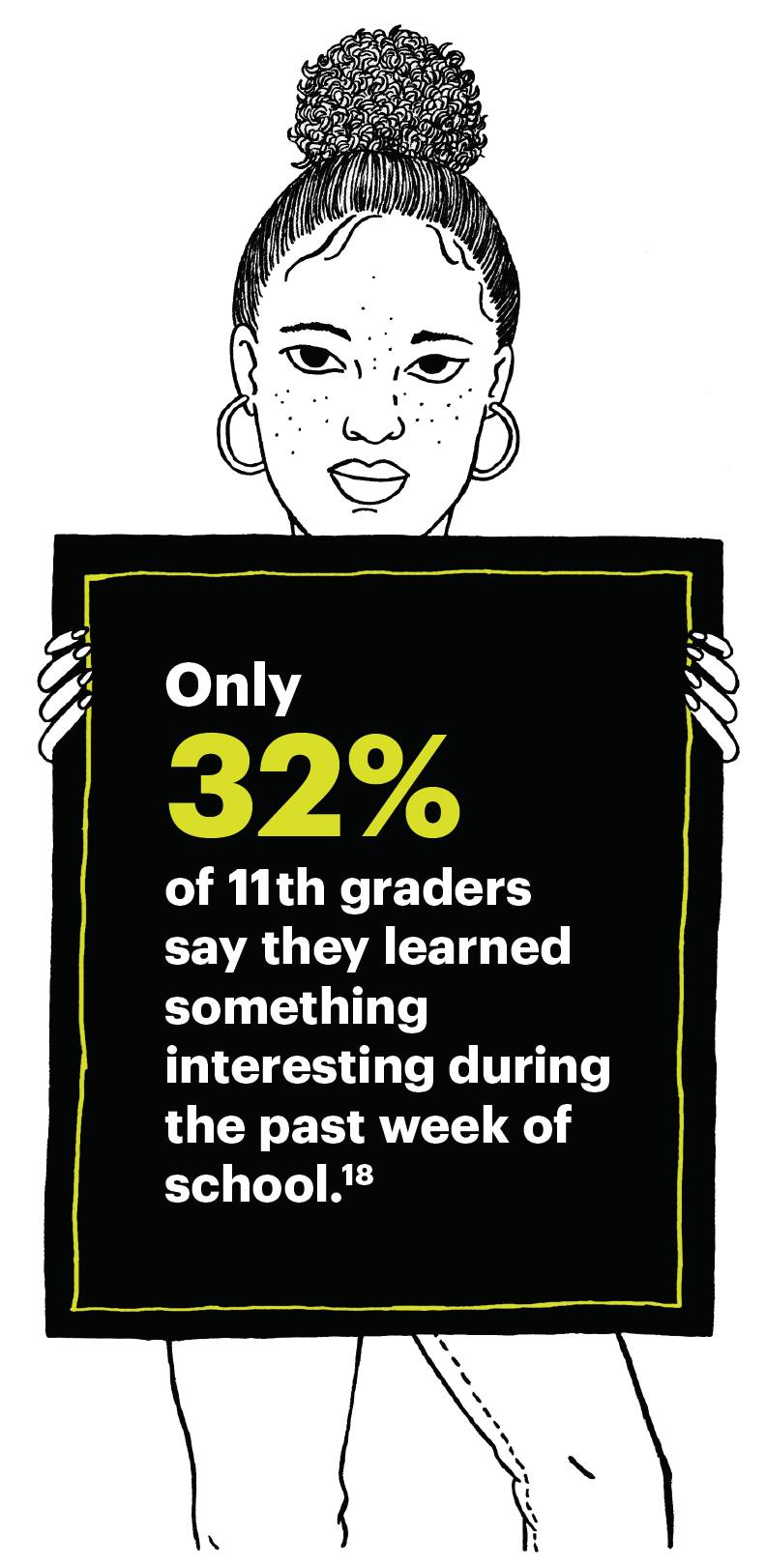

For many students today, a high school diploma lacks the meaning it should have. The route to earning a diploma is too often unengaging, uninspiring, and unchallenging. And, once obtained, a diploma doesn’t guarantee that the graduate has mastered essential knowledge, skills, and competencies and has a viable pathway to the jobs of the future. (See below: “A Long Way to Go: Do diplomas signify preparation for college and careers?”)

State leaders can and must flip that reality. The route to earning a diploma should be challenging, engaging, and inspiring. Once earned, a diploma should signal that a student is truly prepared for college and for the future of work. By taking these eight steps, state leaders can make diplomas more meaningful for all future graduates:

- Develop a profile of a graduate

- Align course requirements with college admissions

- Make rigorous courses widely accessible

- Redefine “course” to break free from seat time

- Challenge students to take college-level courses

- Modernize career preparation

- Support students

- Align accountability

Do diplomas signify preparation for college and careers?

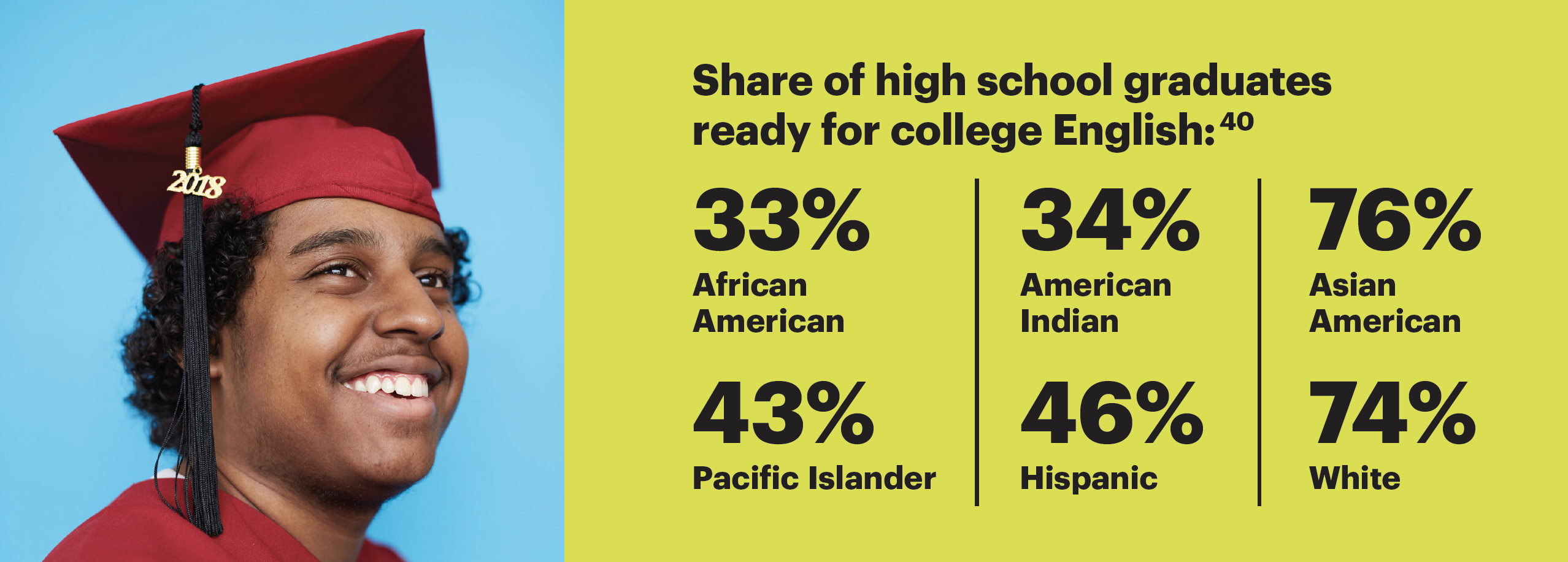

Sometime during the past decade, virtually every state in the nation revised its academic standards to align with the demands of postsecondary education and work. Dubbed “college and career ready” standards, these standards were aimed at ratcheting up the quality and rigor of high school instruction in order to ensure that high school graduates were prepared either to enter a community, technical, or four-year college without the need for remediation, or embark on a fulfilling career.

Available data suggest that we have a long way to go in achieving that mission. In most of the country, high schools still resemble the “shopping mall high schools” decried in the second report of the Study of High Schools issued in 1985: schools that, like their commercial counterparts, seek to satisfy their student consumers with a wide range of course choices and take no position on which choices are most worthwhile.19

For example, despite the adoption of college and career-ready standards by virtually every state:

Given the absence of aligned policy in most states, it is hardly surprising that states are all over the map when it comes to current performance on measures of college readiness. The share of graduates completing a course sequence that matches their state’s definition of college and career readiness, for example, varies from a low of 14 percent in Hawaii to a high of 89 percent in Nebraska.22

State-reported data on completion of college-ready courses and performance on college-ready assessments often send contradictory messages, raising serious questions about the quality and honesty of existing measures—not to mention of high school course titles.23

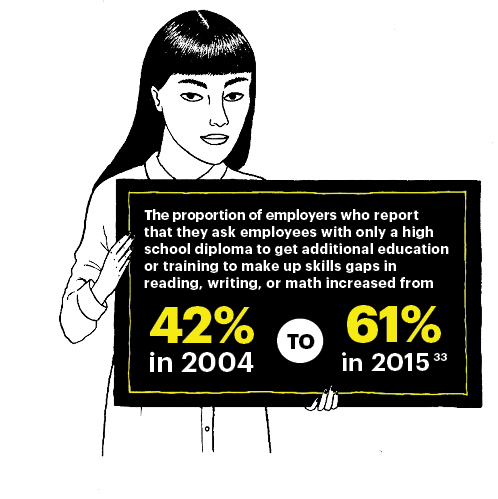

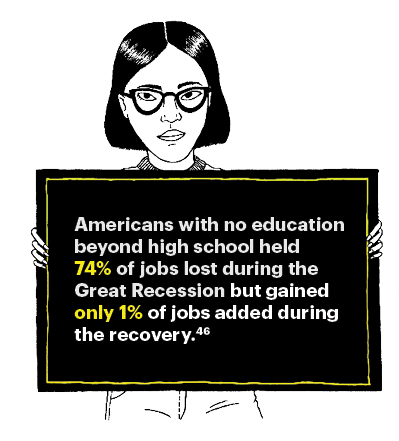

The largest business organization in the United States—the U.S. Chamber of Commerce—made it very clear in its recent report on the subject that the requirements of college- and career-readiness have converged: students who are not college-ready are not career-ready, either. Indeed, the Chamber suggests the need to move from the either/or approach of the past to a concept of “Career-Ready = College-Ready PLUS.”24 By that measure, these data suggest we have a really long way to go.

Over the past decade, most states have refreshed their standards for what high school students should know and be able to do in core academic subjects. Now they can take the next step by defining the broader set of skills and competencies students will need for success after high school, such as self-discipline, initiative, resilience, creativity, and problem-solving.

The first step is to bring students, parents, teachers, business leaders, and community leaders together to ask the question: What skills and knowledge do students need to be successful in college, career, and life? Along with research on skill demands for the jobs of the future, those conversations can become the basis for creating a “profile of a graduate.”

Virginia, for example, recently developed a “Profile of a Virginia Graduate” to describe “the knowledge and skills that students should attain during high school in order to be successful contributors to the economy of the Commonwealth, giving due consideration to critical thinking, creative thinking, collaboration, communication, and citizenship.”25 The profile describes four areas of preparation: content knowledge, workplace skills, community engagement, and civic responsibility, and career exploration.

Wherever possible, state leaders should raise the voices of students and give high school students a seat at the table. The voices of high school students—their experiences, hopes, and aspirations—can serve as a North Star when exploring the kinds of learning opportunities that can best help today’s teenagers prepare for the future of work.

Critically, state leaders developed Virginia’s profile with extensive input and feedback from stakeholders across the state. In fact, the initiative was prompted by the voices of students and families who told the state board of education that “earning a diploma should be about more than passing a prescribed series of courses and tests.”26

XQ has developed a resource that states can use as they begin work on their own graduate profile—a set of Learner Goals and Learner Outcome Areas that aim to develop students who are deeply engaged in their own learning and fully prepared for all that the future has to offer.

Graduates who meet the Learner Goals will be fully prepared academically and well-equipped with the knowledge, skills, and mindsets all young people need in order to thrive in postsecondary education, the workplace, and adult life. The XQ Learner Outcome Areas further spell out the literacies, knowledge domains, ways of thinking, collaborative capacities, and habits of lifelong learning our high school students need to develop. Together, they illustrate how deep, rigorous, and interconnected high school learning needs to be.

Find XQ Learner Goals and Learner Outcomes here: bit.ly/learnergoals

In San Diego, California, students in High Tech High’s six high schools are proud to showcase their learning. High-quality student work—the product of hours of revision, toil, and working collaboratively through challenges—is on display everywhere. Field studies, community service, academic internships, and consultation with outside experts connect students’ learning to the world beyond school. Students are encouraged to take risks with their learning and to use their mistakes as opportunities to develop resilience and persistence. High Tech’s elementary, middle, and high schools share a common intellectual mission and commitment to deeper learning. The rigorous curriculum meets the admission requirements of the University of California, and 98 percent of graduates go to college, most of them enrolling in four-year institutions.

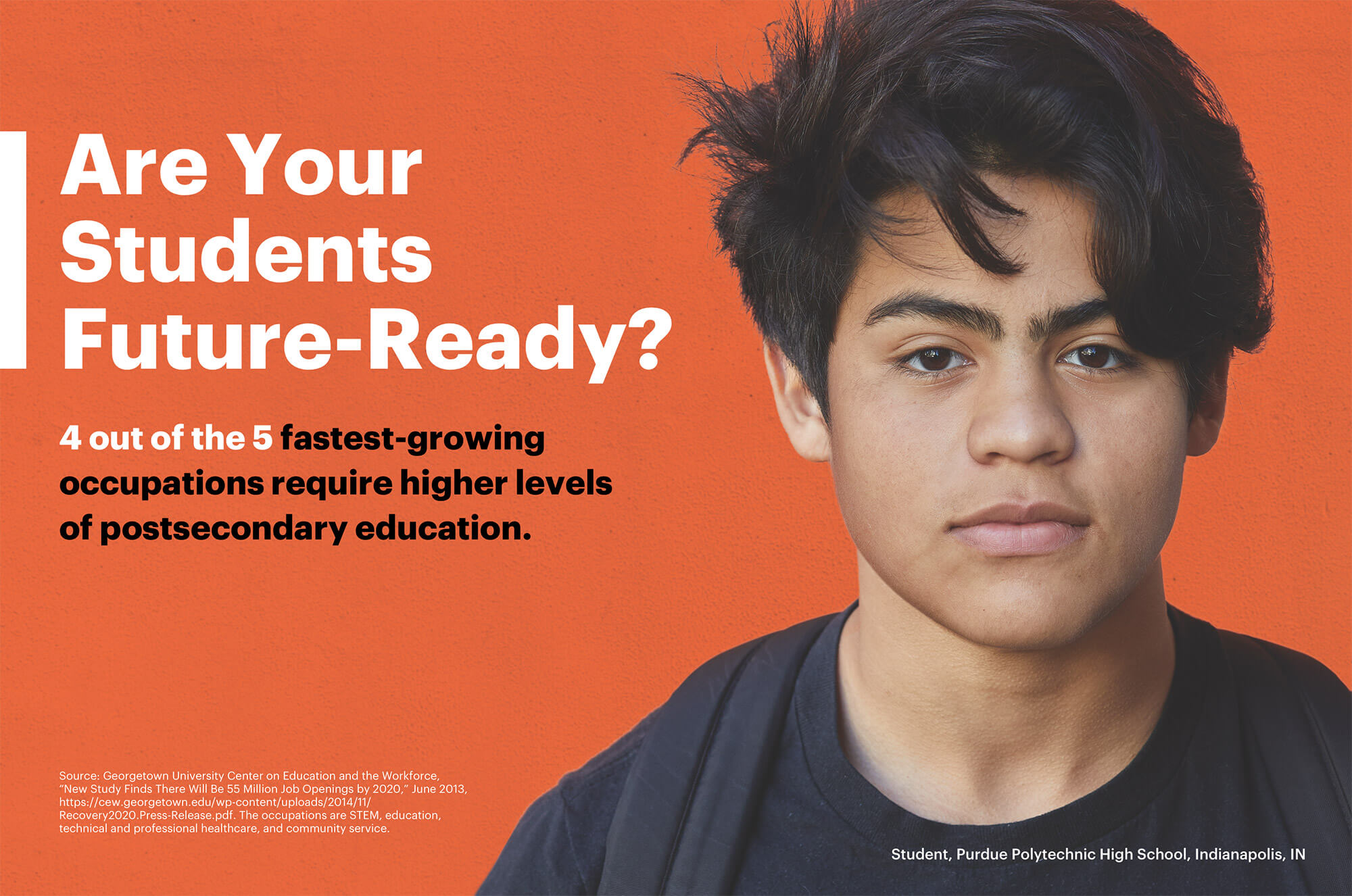

Students should have confidence that if they put in the work to earn a diploma, they will be fully prepared to take the next steps necessary for postsecondary education and the jobs of the future. In most states, students can’t have that confidence now. Even though more than 80 percent of students want to go to college, only about half of America’s high school graduates complete the courses necessary to be prepared for college or advanced postsecondary career training by the time they earn a diploma.27

One step state leaders can take is to require all students to complete courses that will prepare them for postsecondary success. That typically would involve aligning the coursework requirements for earning a diploma with the specific set of courses required to apply to your state’s public university system. States that have modernized CTE offerings can also require the completion of one career-focused course sequence. Some states have multiple diploma options, some of which fully prepare students for college and careers, and some of which do not. At a time when virtually all students will require postsecondary education and training for good jobs in the modern economy, these states should revisit whether continuing multiple diploma options makes sense for students.

2/3 of high school graduates who go on to community college and 40% of undergraduates in four-year colleges have to take at least one remedial course28

In states that retain multiple diploma options, leaders should make the diploma that requires full college- and career-ready coursework the expected “default” track for all students, requiring a formal opt-out procedure if families choose a less rigorous diploma pathway. States that have enacted such default or opt-out policy—with support for students to complete rigorous coursework requirements—tend to achieve much greater equity in student attainment of college- and career-ready diplomas.29

For example, Indiana’s Core 40 policy raised expectations by making a college-ready course sequence—the same course sequence required for entry into Indiana’s public universities—the default pathway for all students beginning in 2007. The policy also established a formal procedure for families to opt-out of the Core 40 diploma and instead complete coursework for a general diploma. To opt-out, the student, the student’s parent or guardian, and the student’s high school counselor must meet and agree that a general course sequence and diploma better meet the student’s educational needs.

To reinforce the importance of taking the more rigorous pathway, Indiana also made an explicit promise to its low-income students: Complete a Core 40 diploma and meet other financial aid and grade requirements, and you can receive up to 90 percent of approved tuition and fees at eligible colleges. Today, 87 percent of Indiana’s graduates earn at least a Core 40 diploma, including 84 percent of African American students, 85 percent of Hispanic students, and 87 percent of white students, as well as 80 percent of low-income students.30

Transparency and accountability matter here, too. States with multiple diploma options should publish data on graduation rates for each diploma type, including the percentage of students overall and in each racial and ethnic group, and hold schools accountable for closing gaps over time. And they should take the extra step, as Indiana does, of publishing data on postsecondary outcomes for graduates who earned different types of diplomas.

The Future of Work is Learning and Adapting

XQ learners are students who are deeply engaged in their own learning and fully prepared for all the future has to offer. The XQ Learner Goals are a blueprint, not a prescription. They are meant to illustrate how deep, rigorous, and interconnected XQ learning really needs to be if young people are to be prepared for the opportunities and demands of a rapidly changing world.

— Heather E. McGowan, Innovation Strategist

Make rigorous courses widely accessible

Many students can’t even take the courses that prepare them for college and good jobs because their high schools simply don’t offer them. Nationwide, only 60 percent of high schools offer physics, while 73 percent offer chemistry and 80 percent offer Algebra II. And students of color have even less access to such courses. Only 51 percent of high schools with high black and Hispanic enrollment offer physics, while 68 percent offer chemistry and 74 percent offer Algebra II.32

State leaders can enact policies requiring districts to offer a rigorous high school curriculum. And they can expand access to the courses students need through statewide initiatives that provide alternatives for students to take courses outside their schools.

For example, Rhode Island’s Advanced Coursework Network enables high school students to earn credits by completing courses offered by other districts in the network, community-based organizations, state workforce training programs, or institutions of higher education when those courses are not available at the student’s own high school. The initiative ensures quality control through its course proposal and approval process.

States can maintain high standards and college-ready coursework requirements while opening up room for innovation in high school teaching and learning. One way to do that is by revising the formal definition of a high school “course” to broaden the ways in which students can learn and demonstrate their learning in order to earn credits and, ultimately, a diploma.

High school students could, for example,

earn credit for learning that takes place in a business or other community setting. They could earn credit for completing challenging collaborative projects or for demonstrating their mastery of knowledge and skills at their own pace. Such learning experiences are often deeply engaging for students, and they can help students develop the broader competencies—such as self-discipline, initiative, resilience, creativity, and problem-solving—called for in a state’s profile of a high school graduate.

earn credit for learning that takes place in a business or other community setting. They could earn credit for completing challenging collaborative projects or for demonstrating their mastery of knowledge and skills at their own pace. Such learning experiences are often deeply engaging for students, and they can help students develop the broader competencies—such as self-discipline, initiative, resilience, creativity, and problem-solving—called for in a state’s profile of a high school graduate.

For example, in 2016 Rhode Island revised its state diploma system so that, beginning with the class of 2021, students must successfully complete 20 courses in various subjects and pass one performance-based assessment to earn a diploma. At the same time, leaders redefined the concept of a course in state regulations to de-emphasize classroom seat time and instead focus on proficiency in meeting state standards. That change created new flexibility for courses to be interdisciplinary and to include project-based learning and experiential learning opportunities such as internships and apprenticeships. Rhode Island’s approach provides students with more choice in how, when, and where they learn and demonstrate their learning.

Let’s be clear. This isn’t about replacing what goes on in the classroom with less demanding experiences outside of it. This is about integrating innovative approaches to teaching in the classroom with opportunities for students to develop practical, concrete skills in real-world settings. And it’s about awarding credit for learning—demonstrated learning—no matter where or when the learning takes place.

RHODE ISLAND: REDEFINING “COURSE” TO GET BEYOND SEAT TIME

According to Rhode Island’s “Secondary School Regulations,” a course is a “connected series of lessons that: a. Establish expectations defined by recognized content standards; b. Provide students with opportunities to learn and practice skills; and, c. Include assessments of student knowledge and skills adequate to determine proficiency at the level of academic rigor required by relevant content standards.”The state’s “Secondary School Regulations Reference Guide” provides additional clarification:

Challenge students to take college-level courses

We know that a college education changes the trajectory of a young person’s life. That’s why— on top of the college preparation courses discussed earlier—every student deserves an opportunity to take college-level coursework in high school through dual enrollment, early college high schools, or AP and IB courses.

Dual enrollment programs enable students to take college-level courses and earn college credits while still in high school. These programs provide engaging and meaningful coursework that helps students develop skills, gain knowledge, and build self-reliance and confidence to succeed in college and beyond. Research has proven that dual enrollment boosts college preparation, participation, and completion.34 It also helps families reduce the time and cost for students to earn postsecondary degrees and embark on well-paying careers. But sadly, many students simply don’t have access to these programs. Smart state policy can change that.

Like dual enrollment, AP and IB courses enable high school students to take college-level courses, but students earn postsecondary credits by taking and passing curriculum-based exams. States can provide resources to expand AP and IB courses—especially in schools with high percentages of low-income students and students of color, where students traditionally have had less access to these demanding courses—and pay the costs for low-income students to take the end-of-course exams to earn postsecondary credit.

Early college high schools also have a proven track record of preparing students for college and life.35 Located primarily on college campuses, early college high schools enable students to earn two years’ worth of college credit, or a full associate’s degree, along with their high school diploma. North Carolina has grown the number of early college high schools to 83 through its innovative high school program.

As state leaders encourage and support access to these types of opportunities—whether dual enrollment, AP and IB, or early college—they also must ensure that all students can participate regardless of income or geography. The state education agency should monitor participation to ensure programs are available on an equitable basis. Districts should be required to communicate with all families about the opportunity. And additional funding should be provided to avoid creating financial incentives for school districts to discourage participation. State leaders should also take action to guarantee that students can transfer the credits they earn to other public institutions of higher education in the state.

Bard Early Colleges is a frontrunner in providing high school students access to college-level courses, particularly low-income students and students of color. Graduates earn both their high school diplomas and associate’s degrees, with up to two years of transferable college credit. With eight locations in five states, Bard Early Colleges are increasing college access, affordability, and completion for more than 2,300 students each year.

Ohio doubled the number of students participating in dual enrollment—from 31,000 to 68,000—in just two years through its new College Credit Plus program. College Credit Plus established a mandatory, uniform approach to dual enrollment, replacing a policy that allowed a patchwork of uneven dual enrollment opportunities across districts. College Credit Plus is free to families when courses are taken through public institutions of higher education. Participating families saved about $260 million in future college tuition costs during the first two years of the program. The state requires school districts to hold a College Credit Plus information night for parents each year, and it prohibits them from discouraging eligible students to participate.

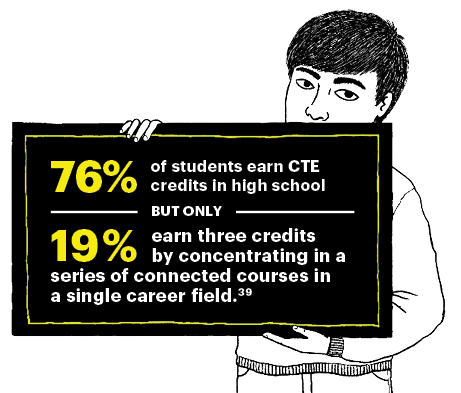

Modernize career preparation

Students who participate in high-quality career and technical education (CTE) are more likely to graduate, earn industry credentials, enroll in college, and have higher rates of employment and higher earnings.36 But the key is ensuring that these CTE programs are truly high quality and lead to good jobs in growing fields. And students who “concentrate” by completing three or more CTE courses in a single field reap greater benefits than those who take scattershot CTE course offerings.37

Modern CTE best practices are carefully designed to combine engaging academic learning with focused preparation to succeed in high-demand fields such as health services, advanced manufacturing, and digital technology. Because good jobs increasingly require at least some postsecondary education or training, effective CTE programs also prepare students to continue their education and training in college or advanced apprenticeships.

Tennessee conducted a thorough overhaul of its state-approved CTE courses of study, offering more challenging and relevant coursework. The state discontinued nearly 100 courses of study that were found to be low-quality or poorly aligned with industry needs and adopted more than 100 new or revised courses of study such as mechatronics and electromechanical technology in advanced manufacturing. Tennessee now annually reviews all CTE courses of study, requiring that each one demonstrate alignment with secondary standards, postsecondary opportunities, and the most recent labor market data. This is what quality education should be about: equipping students for the real world.

State leaders can also support work-based learning (WBL) opportunities that help students explore careers while applying their learning and building new skills. But as with CTE broadly, state leaders must take steps to ensure that work-based learning opportunities are high-quality, focused on job sectors with expanding demand, and help students build the kind of skills defined in the state’s profile of a graduate.

For example, through a budget line item, Massachusetts funds a statewide intermediary structure called Connecting Activities that engages 16 local workforce investment boards to connect schools and businesses in public-private partnerships to provide students with skill-building, work-based learning opportunities. Connecting Activities also collects and publishes data on students’ WBL experiences to ensure alignment with good jobs in growing industries such as STEM.

Tennessee overhauled its WBL policies from 2013 to 2016, adopting a new statewide framework for work-based learning and issuing a new “WBL Implementation Guide” and a “WBL Policy Guide.” The policy guide establishes criteria under which students can earn high school credit for certain kinds of work-based learning connected to rigorous practicum courses. Tennessee piloted its new approach to work-based learning in five communities before scaling it statewide.

Results of a national Gallup poll released in April 2018 show widespread support for expanding work-based learning opportunities such as job shadowing and internships as a way to prepare students for the jobs of the future. And that support was remarkably consistent across political affiliation, with Democrats and Republicans equally likely to suggest work-based learning as the best way to prepare students for the modern workplace.38

Support students

Students will need support to meet rigorous diploma requirements, to develop the competencies in the graduate profile, and to make informed plans to succeed in a rapidly changing economy.

First, some students will need extra support to meet college- and career-ready expectations. States can support students by requiring screening to identify those who are significantly behind in literacy or numeracy and targeted interventions to accelerate student progress. And they can require and fund early warning and intervention systems that monitor research-based predictors of on-time graduation—such as attendance, suspensions, grades, and credit accumulation—and intervene with targeted supports for students who fall off track.

Second, all students will need better-personalized guidance to understand diploma requirements, to explore post-secondary college and career opportunities, and to plan for a successful future. Washington state now requires all students to develop an individualized High School and Beyond Plan in middle school and to update that plan throughout their high school careers. The plan must include an aligned high school course-taking strategy as well as a “Personalized Pathway” that considers CTE and postsecondary dual enrollment opportunities. The state provides a range of resources to enable students to make the most of the planning, including a digital planning platform and a comprehensive curriculum called Career Guidance WA.

Finally, students and families will need regular feedback on whether students are developing the kinds of competencies called for in the graduate profile, and that will require providing their teachers with new kinds of formative assessment strategies. For example, after adopting its new graduate profile, Virginia launched an initiative to provide districts with technical assistance to develop performance-based assessments that allow students to demonstrate their knowledge through hands-on experience while employing critical thinking and communication skills across one or more subject areas.

To support its proficiency-based graduation policy, Rhode Island launched an initiative called Scaling Up Proficiency-Based Graduation, through which a network of high schools collaborated on a set of common performance assessments and ways to implement high-quality assessment practices. In addition, last year, Rhode Island launched a new initiative called Learning Champions that brought together outstanding educators from across the state to design tools for defining and assessing mastery of competencies. The Learning Champions have crafted frameworks with proficiency indicators and scoring criteria for the cross-curricular skills of communication, collaboration, problem-solving, research, and reflection and evaluation. They are currently designing sample assessments aligned with those frameworks.

Redefining what it means to be prepared and opening up new ways for high school students to meet that definition should mean getting more serious about standards and accountability, not less. In addition to investing in new approaches to assessment, such as those described earlier, state leaders will need to carefully consider state systems for holding high schools accountable for performance. Existing accountability systems, which are still preoccupied only with time-based credits and testing, will have to be brought into line with both the broadened goals of high school and additional forms of measurement.

Already, some states are moving in this direction by including a broader range of measures in their accountability systems for high schools. And some districts, including California’s CORE districts, are even further ahead, developing, testing, and now using in their own accountability systems measures of real-world skills like self-discipline and growth mindset.

Clearly, all of this requires strong state involvement and a serious investment in local capacity to measure students’ attainment of knowledge, skills, and competencies in ways that support consistency across schools and districts. It also requires acknowledging the uneven capacity among school districts and deliberate action to shore up the relevant capacities of struggling districts in order to make sure that all students benefit from these changes, rather than just some.

Each state needs a deliberate plan of action for developing new kinds of measures for its high school learner goals and testing them out to ensure they are valid and reliable and do not impose unintended consequences for students. Those new measures can be used to inform decisions about instruction at the local level, and some measures may be suitable to incorporate into statewide accountability systems after significant testing and validation over time. States can embrace the flexibility offered by the federal Every Student Succeeds Act while still ensuring that high schools are held accountable for academic achievement and other educational outcomes of all students—including students from low-income families and students of color.

- Get Teachers the Tools They Need

State leaders can’t provide high school students with new ways to learn—and new ways of demonstrating mastery of knowledge and skills—without support, enthusiasm, and buy-in from teachers and school leaders. Re-imagining high school calls on educators to re-imagine their roles in classrooms and schools.

Across the country, there are statewide debates around the level of compensation for teachers. In many states, teachers’ compensation is not in line with the compensation level for other professions requiring similar levels of education.41 As interest in the profession drops and teacher turnover remains high, state and local leaders will need to be attentive to this issue and think through innovative strategies to elevate the profession, including new strategies for educator recruitment, preparation, and advancement.

We recommend a set of policy actions focused on getting educators the instructional resources and professional knowledge they need to take on the kind of high school transformation described in this guide. But these actions should be seen as part of a much more comprehensive agenda.

To build a strong, vibrant, well-supported education profession, fully equipped to meet the demands of the 21st century, we encourage you to take three steps:

- Increase access to high-quality learning tools and resources

- Mobilize expertise and spur investment to create new solutions

- Help educators navigate the market

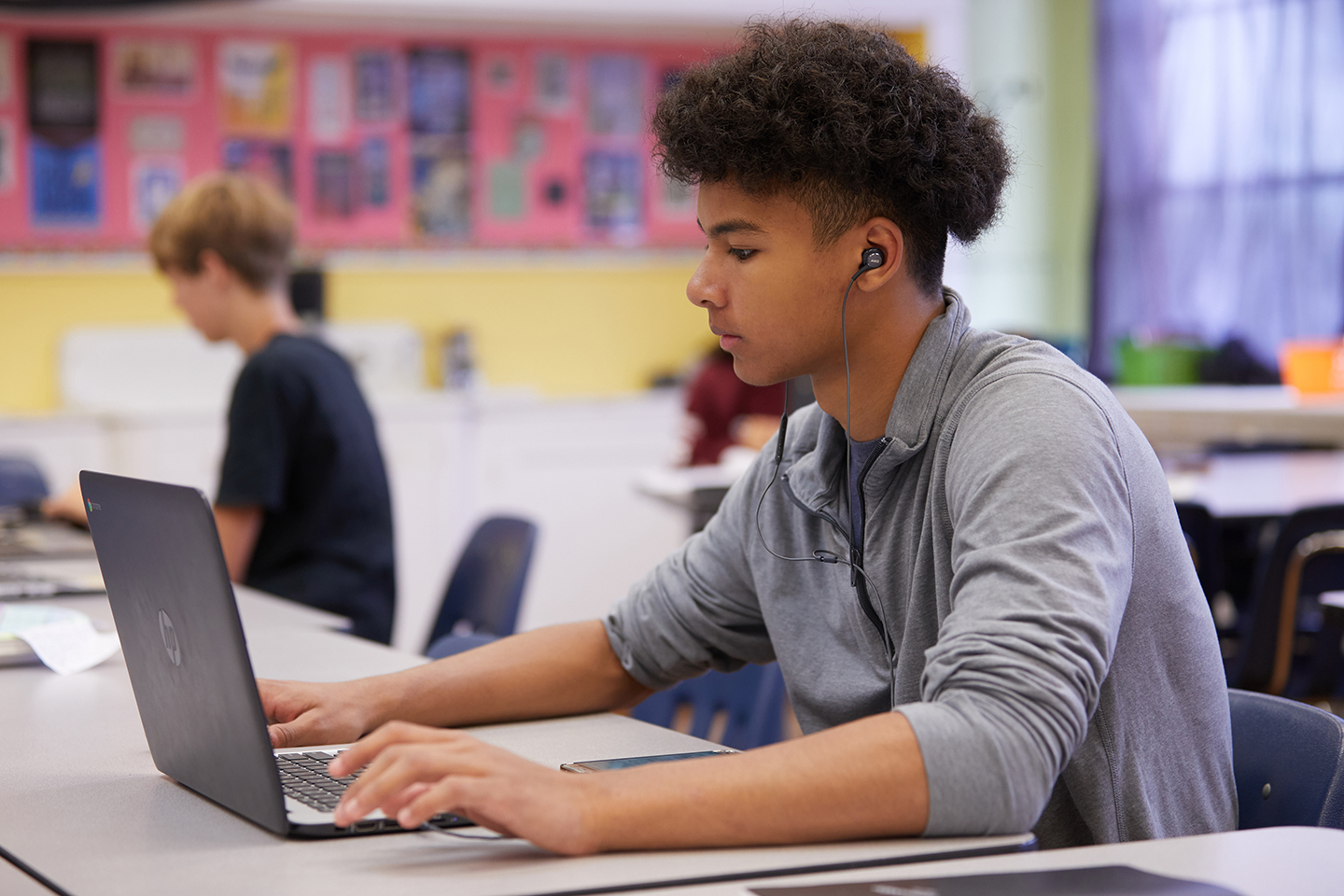

New approaches to teaching and learning can free teachers and students alike from the four corners of the textbook. But teachers lack access to the tools and technologies to address long-standing challenges and breakthroughs to new kinds of teaching and learning. For example, educators frequently remark on big gaps in the availability of high-quality high school curricula, the lack of platforms and repositories to scale up project-based learning, and a dearth of effective instructional tools to accelerate progress for students who enter high school significantly behind.

Schools are often inundated with options. Yet, as new tools and materials become available, local educators have few opportunities to learn about them, compare them, and make informed decisions about what will work best with their students in their own schools and classrooms. At the same time, there are still big gaps in the market, particularly with respect to curricula and technology-enhanced tools that are necessary to make next-generation instruction a reality. The sector lacks the robust R&D infrastructure necessary to meet new demands and accelerate learning to close achievement gaps. Those problems demand bold leadership to mobilize expertise, spur investment to create new solutions, and help local actors navigate the market.

Research and development account for only 0.2% of total K-12 education expenditures. That’s far lower than the overall 2.9% invested in R&D across all U.S. sectors. And it’s one-fiftieth the R&D investment rate in highly innovative sectors.42

State leaders can use a strategy called demand aggregation to encourage private investment to fill gaps in the supply of high school curriculum and learning resources. They can do that by demonstrating a widespread shift in high school approaches to teaching and learning that signals an increasing demand for new kinds of curricula and instructional resources. For example, a state that holds a summit on high schools of the future could incorporate a hackathon or prize announcement and cite survey data to send a strong signal about the growing number of districts or high schools that are looking to the market for certain kinds of tools and resources.

Groups of districts can also be encouraged to work together to send signals to the market. For example, Project Unicorn is an initiative started by a group of school districts jointly pledging to purchase technology-based products only if the vendors make their systems interoperable.

By 2020, 2/3 of all U.S. jobs will require postsecondary education or career training beyond high school.43

States have used hackathons and design competitions to unleash creativity and inspire breakthrough solutions in sectors outside education. For example, since 2014, the Colorado secretary of state’s office has organized Go Code Colorado competitions to challenge multidisciplinary teams—developers, designers, business and marketing professionals, analysts, entrepreneurs, and other “big thinkers”—to turn public data into useful business insights and technology-driven tools. Pennsylvania’s statewide hackathon, Code4PA, harnesses technical talent to leverage state and local data sets to increase transparency and efficiency in public engagement with the government. This year’s Code4PA hackathon will challenge teams to turn data into insights for fighting Pennsylvania’s opioid epidemic.

Why not harness the same kinds of talent to create solutions in education? State leaders can sponsor hackathons and competitions that challenge interdisciplinary teams to fill gaps in high school curricula, create platforms to support project-based learning, and develop technology-infused approaches to accelerate student learning for students who enter high school behind grade level in reading or math. The first step is to invite educators to identify the biggest challenges to high school transformation, including the biggest gaps in learning resources, that hackathons and competitions can help address. Educators should also be invited to participate in the interdisciplinary teams that create solutions. State leaders also can offer prizes to mobilize cross-sector talent and expertise to create breakthrough solutions and accelerate innovation in high school education. Unlike grants or direct investments in research and development, prizes are performance-based and can spark widespread interest and participation among a broad, diverse pool of talent. They also can help raise the profile of an issue or problem by attracting press coverage and attention on social media.

Improving education ranks second out of 19 diverse issues that adult voters want elected officials to prioritize in 2018.44

Invest in open educational resources.

Open educational resources (OER) are no-cost, public-domain educational materials, and resources that are introduced with an open license, making them legal for free use, copying, sharing, or adapting. For example, the New York State Education Department launched EngageNY as a statewide effort to create free OER curriculum materials aligned with the state’s K-12 academic standards. The materials have proven so popular that they are used widely by educators across the United States.45

A state could use a similar approach to fill gaps in high school curricula and learning resources that can help scale student-centered, personalized, project-based learning strategies across high schools.

Help educators navigate the market

State leaders can provide information to help local educators navigate the market by bringing educators together to conduct an independent quality review of instructional tools and materials and then creating incentives to use higher-quality materials. For example, Louisiana enlisted teacher leaders from across the state to review instructional materials and rank them into three tiers, with tier 1 being “exemplifies quality,” tier 2 “approaches quality,” and tier 3 “not representing quality.” While districts remained free to select instructional materials best suited to local needs, their choices could be informed by the statewide review and the rubrics used to judge the materials. The state also extended statewide contracts to publishers of instructional materials earning the Tier 1 rating, which enabled districts to adopt those materials at discounted prices without having to go through local procurement procedures. States can also help districts and high schools adopt digital platforms that teachers can use to personalize each student’s learning experiences and keep track of student progress. States will want to make sure that parents and students have full access to information on the platform—an important element for enhancing student ownership of learning—while ensuring that federal and state laws regarding student data privacy are strictly observed.

Personalize professional learning

Current high school teachers also need opportunities to learn new kinds of skills for leading student-centered classrooms. But outdated, one-size-fits-all professional development approaches are ill-suited for learning how to teach students in more personalized, competency-based ways. A new approach called micro-credentialing can provide an innovative solution.

Micro-credentialing allows teachers to demonstrate highly specific professional competencies that they can learn and master in more flexible and personalized ways—often using online resources coupled with on-the-job practice. To earn a micro-credential, teachers must submit evidence, such as a video of classroom instruction or student work, showing that they have mastered the skill in question. Most micro-credentials come in stacks of related skills, enabling teachers to progress at their own pace while stacking credentials to demonstrate growing expertise in a broad area such as performance assessment or personalized learning.47

States could begin by permitting teachers to meet continuing education and re-certification requirements by earning micro-credentials rather than by spending seat time in traditional professional development courses and workshops. Some states already allow teachers to use micro-credentials to comply with continuing education or re-certification policies, and a handful of states are conducting formal pilot programs to test micro-credentialing. State leaders also could direct federal and state professional development funds to support teachers who want to develop competencies for personalized, student-centered learning environments, including obtaining relevant micro-credentials.

STEM jobs will grow by 13% by 2027, compared with 9% growth across all other jobs.

Median earnings in STEM jobs are $38.85 per hour compared with $19.30 per hour across all other jobs.48

Few preparation programs actually prepare high school teachers and principals to work in student-centered environments where learning is personalized, project-based and focused on mastery rather than seat time. States can leverage the significant authority they have over educator preparation and certification to change that.

A good place to start is to develop clear, specific educator competencies for teaching in new learning environments. The Council of Chief State School Officers and Jobs for the Future offers an excellent resource: Educator Competencies for Personalized, Learner-Centered Teaching.

Those competencies cover four domains —instructional, cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. The instructional domain includes competencies that are relevant to teachers’ work in innovative high schools, including the following:

- Using a mastery approach to learning

- Using assessments for learning

- Customizing the learning experience

- Promoting student agency and ownership of learning

- Providing opportunities for anytime, anywhere learning tied to specific learning objectives and standards

- Developing and facilitating project-based learning experiences

- Using collaborative group work

- Using technology in service of learning

States can integrate student-centered learning competencies into their statewide teaching standards and update policies for state approval of preparation programs to align with those standards.

For example, in 2013, the Vermont Standards Board for Professional Educators adopted new professional educator standards to incorporate personalized learning approaches to support diverse learners, including a stronger focus on application of knowledge and skills and improved assessment literacy for educators.

Moreover, to ensure that teachers have the school-level supports and systems they need to take on these challenges, states should update the competencies expected of school leaders and incorporate those expectations into policies governing school leader preparation and certification. Creating truly student-centered high schools will require providing school leaders with the ability to develop and sustain complex systems for managing time, staffing, personalized curriculum, on- and off-campus learning experiences, community and higher education partnerships, student assessments, data gathering and analysis, and sophisticated use of learning technology.

States also can support fellowships and teacher residency programs embedded in innovative high schools with personalized, project-oriented, competency-based learning environments. Teacher residency programs allow a prospective teacher to apprentice with an effective master teacher for up to two years while completing coursework tailored to the local context. Similar programs for school leaders can increase the pool of high school principals who bring the requisite skills and an innovative mindset to the job.

Finally, states can create alternative certification routes to enable innovative high schools to employ adjunct faculty members who are professionals in high-growth industries and fields outside of education to support career-readiness education.

Iowa BIG: Linking Learning to Projects that Benefit the Community

In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, educators and community leaders have come together to expand the very concept of high school, convinced that a rigorous education should never have to be a boring one. Iowa BIG attracts students from across the region to learn by taking on projects that will benefit their community. Students work hand-in-hand with members of local businesses, nonprofits, and government agencies to solve a problem, meet a need, or design a solution—from redesigning a local elementary school to developing a drone that can measure waste in river ways. Teachers help students identify what they can learn during the project, then use a digital platform to track the state academic standards in which students demonstrate mastery so they can earn credits toward graduation.

High School and the Future of Work

Sign up for our newsletter

Get the latest educator insights and practical classroom tips every other week, direct from the XQ community

Follow us to #RethinkHighSchool