A Black Man Reflects on Sonia Lowman’s film Black Boys

The film ‘Black Boys’ paints a picture of the racial inequities that affect Black men in our country. Here’s one man’s reflection on the film.

As a Black man, my success seems remarkable—and to a certain degree, it is. Last spring, I graduated with honors from the University of Arkansas with two degrees: political science and African and African American Studies. Without context, I seem like a man with incredible ambition and determination. However, by simply praising my success non-Black folks do not recognize the structural barriers I faced because of the color of my skin. Through perseverance and tenacity, as well as mentorship, I pulled myself up to face these barriers head-on and succeeded in structures unwilling to allow my passage.

The journey to my liberation was not an easy one. It required me to learn how my mind, body, voice, and heart were regulated and controlled by a world that functioned on their exploitation. I had to re-educate myself to see these regulations as unjust. Luckily, I had a mentor, Dr. Caree Banton, who helped me understand that I had learned to view myself through a lens painted by Whiteness. I had to learn that Whiteness was not something to be achieved and that no matter how White I presented myself—in my eloquent speeches and button-down shirts—I would never close the economic and social gaps between me and my Whiter counterparts.

Instead, my freedom and equality rested in my willingness to accept and embrace my Blackness. A process that came through an educational journey of my own. I needed thinkers like James Baldwin and Audre Lorde to give language to inklings I had about structural racism—things I knew to be true but couldn’t express myself. In doing so, their words offered the escape from the confines of the White-centric world in which I lived.

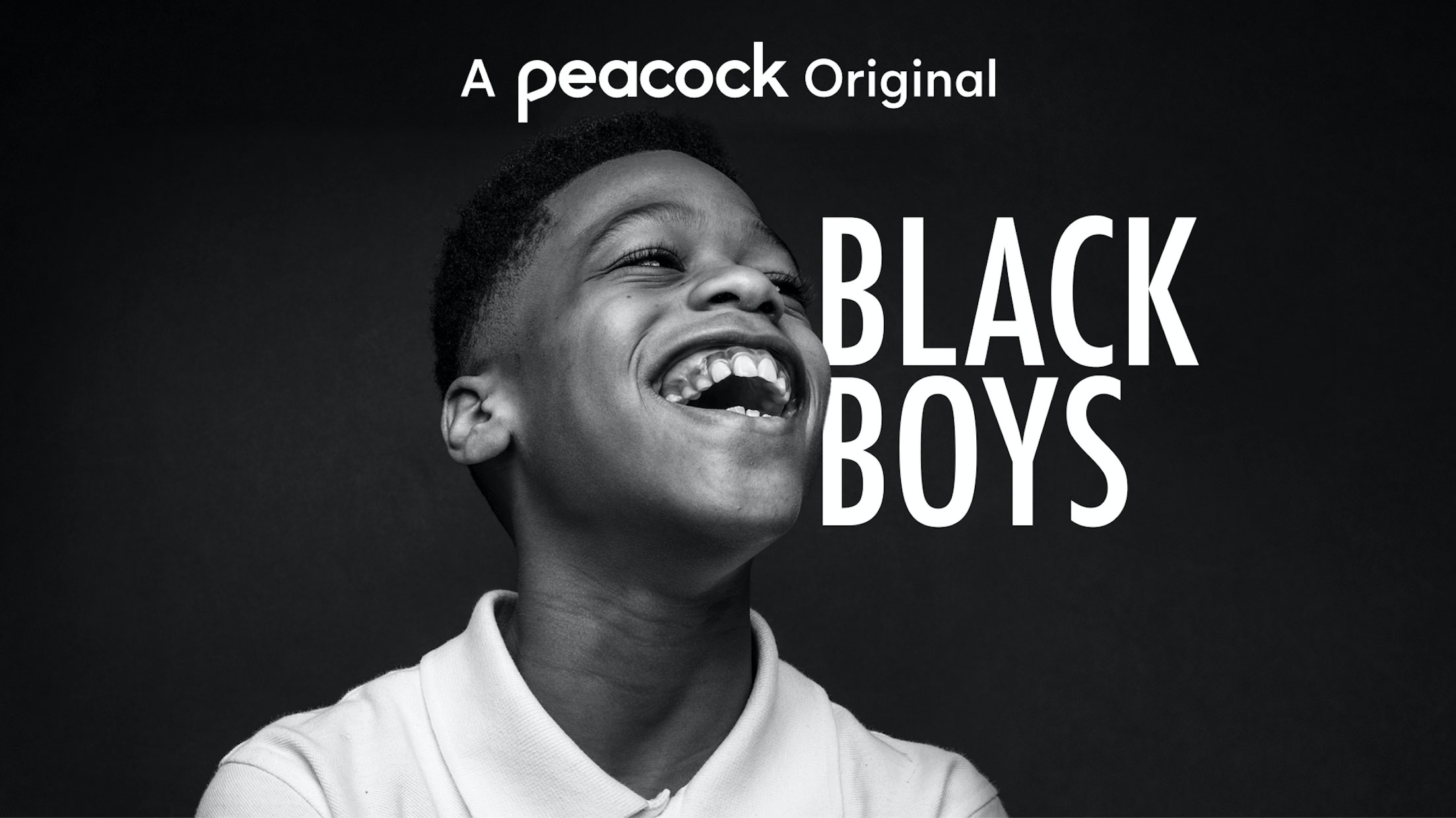

Recently, I watched this journey of personal liberation—of unlearning and relearning—played back to me in Sonia Lowman’s film Black Boys, which artfully illuminates the struggles Black boys face throughout self-actualization. The film stirred up painful memories from my own childhood, forced me to confront them, and allowed me to move past them. It continued my endless process of re-education by illustrating how Whiteness informs my time in public education and helped position myself towards liberation.

What is Public Education for Black Boys?

The story of the Black boy in education is a story of built limitations—limitations that come from structures, not within people. It’s a story of few resources and even fewer opportunities. It’s a story of giving kids who are worst positioned to succeed less of everything that matters. It’s not only a story of a lack of funding, but also a story of non-existent representation. It is the story of how the Black body is indoctrinated and made docile through a nefarious footsoldier of White supremacy.

I can’t speak for all Black boys as we are not a monolith, and doing so would deny us personal struggles and individual successes. However, what I will say speaks to my experience in education as well as my observations about communities for low-income communities of color.

My education began in one of the poorest counties in the state of Arkansas. It was a perceived notion, accepted as fact, that members of my community were responsible for our place on the socio-economic continuum. A premise rooted in individualism or this idea that you need to pull yourself up by the bootstraps to move up the socio-economic ladder. For instance, my low-performing school reflected the inability of the students to master the subjects taught by our teachers, and our poor graduation rates were not correlated to a lack of funding or poorly trained teachers. Instead, the onus of our failure was on our work ethic.

In my own education, the lack of quality teachers made it impossible for me to develop into a critical thinker. This void kept me from seeing the injustices and inequities that surrounded me. In many ways, it silenced me. I was oblivious to the structural challenges that thwarted my success, and so I did not speak to things that I felt were wrong.

The sidelining of Black voices continued in my curriculum which further informed how I viewed myself and my possible futures. For most of my time in public education, I did not receive literature that accurately reflected my culture and celebrated my Blackness. Instead, I was given windows into the lives of White people. Even when we read books that touched on oppression, colonization, and racism, we were told the story through the perspective of White protagonists. Scout Finch may be helpful to a young non-Black girl trying to grapple with unjust aspects of the world, but she was far from the solace and representation that I needed in literature.

Disregarding our history, or including it through the eyes of our oppressors, conditions Black boys into thinking that we are unworthy of recognition––that when compared to Whiteness, we don’t measure up. We learn this lesson inside of educational spaces. Blackness, according to textbooks and teachers, is marred by a history of enslavement and criminality. I had no survey of my own history or culture. The only stories of resilience worth sharing seem to be those of World War ll, the American Revolution, and the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout my K-12 education, I was never told that my own history was rich. That it exists beyond the confines of struggle, pain, and strife. I was never reminded that my joy deserved to be shared and protected.

As my voice was silenced in school, I was often told that my body would be my vehicle to drive me out of poverty. Many Black boys just like me, disillusioned by the scarcity of resources, turn to sports as a place of social mobility, a message that permeates every aspect of mainstream media. We weren’t told to be teachers and work to dismantle the systems that tried to relegate us. Instead, we were subject to a calculated and manipulated representation, intended to keep us in our social place. Without the representation of diverse futures, Black boys like myself were denied the freedom to imagine. Our minds were policed. Messages seemed credible to me because I was never challenged to think otherwise.

Today, learning how to use my voice is an arduous process. Years spent in education—being told when and where I could speak—has made it hard for me to be confident in my own words. And, unlearning to silence my voice is not something that happens overnight. I didn’t understand that my voice matters and deserves to be uplifted until adulthood. Black boys often wait for the day for someone to believe in them––to see them as the brilliant Black kid, to recognize them outside of the way they are portrayed. I waited for that day, but it never came.

Believe in Black Children

In education, I never needed a savior. I just needed a believer. Believing in a Black boy or Black girl means being their ally. It means loving them—caring for them in tangible ways. It means being wary of how your allyship may be performative. And, it means moving from an expressed allyship to more aggressive attempts to dismantle systems of racism. For Black children to grow into empowered Black adults, discussion of barriers will not be enough. We have to stop praising Black adults for their resilience and begin to eradicate structures that force them to be strong and rob them of their right to simply just be children.

We need to do more than just care. We need to learn to love our Black students, peers, and friends. It is not enough to tolerate them in the classroom, we need to infuse love for them in every space—public and private. The love will then dismantle the need for Black children to be strong all the time. To create that love, non-Black allies need to unlearn their misconceptions and perceived bias. Black children are taught to hate ourselves and view ourselves through hate. Help us reframe our image by loving us.

Love me as much as you love my culture. Speak up for me, choose me for group assignments, maybe pick me last in PE or for sports teams, uplift my perspective in a class discussion, ask me questions about my weekend from a place of wonder and not judgment. Most importantly, remember that this is sacred and urgent work: the future of Black boys and girls rests on it. Black Boys by Sonia Lowman will be featured in week one of the Global Film Fest, alongside other narratives around the experiences of BIPOC students.