Encouraging Higher Order Thinking Skills in Students

Rigor is one of those ambiguous terms in education where everyone has a different definition. While…

Rigor is one of those ambiguous terms in education where everyone has a different definition. While it can vary widely in practice, rigor means that students are engaged in challenging tasks. Rigorous learning does not mean overly complex activities. Instead, teachers can create the rigor they need by developing learning experiences focusing on students using higher-order thinking skills.

The XQ high schools provide several examples. At Purdue Polytechnic High School in Indianapolis, students built a boat out of cardboard to cross a swimming pool for their passion projects. At New Harmony High School in New Orleans, students wrote original stories imagining a future ravaged by climate change. At Latitude High School in Oakland, California, students built tiny houses for unhoused youth. While all different, each of these projects created authentic learning experiences with rigorous elements that encourage students to apply higher-order thinking skills to their learning.

Through higher-order thinking (HOT) skills, students move beyond memorizing and regurgitating material–instead actively analyzing, evaluating, and creating solutions to showcase their learning mastery.

High school is an ideal time to foster higher-order thinking skills when considering developmental milestones in adolescence. As students enter high school, they are more likely to comprehend abstract thinking, develop unique ideas, and analyze various perspectives different from their own. That’s the idea behind our XQ Learner Outcomes, which activates higher-order thinking by asking students to become original thinkers for an uncertain world, holders of foundational knowledge, and self-directed learners for life.

Because students are entering the classroom at different levels of understanding, planning lessons that target, differentiate, and scaffold HOT skills requires a lot of foresight. However, project-based and inquiry-based learning models are ideal pathways where teachers can effortlessly target those skills. By understanding and defining what higher-order thinking skills look like, teachers can structure their curriculum more easily to teach these competencies to students, empowering them as the next generation of thinkers and creators.

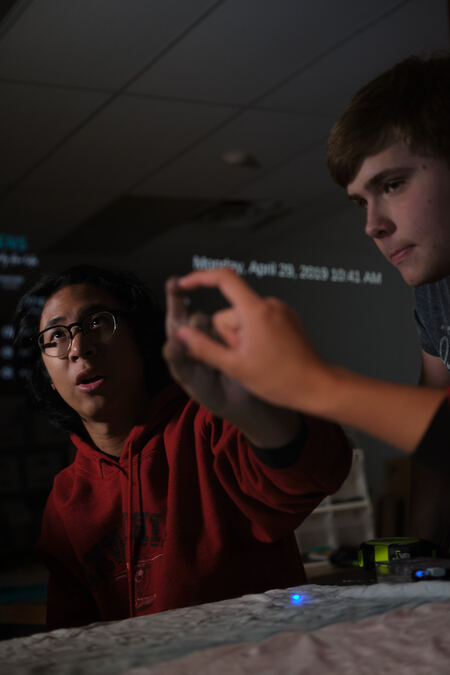

Students at PSI High, an XQ school in Sanford, Florida, create solutions for a local engineering industry by constructing a smart mirror for the offices. (Photo by Maya Richardson)

What are Higher-Order Thinking Skills?

Higher-order thinking is a sequence of thinking skills that moves students beyond rote memorization into more comprehensive levels of thinking. It asks students to take facts and information they have memorized and apply them in a new, active way—like making an inference—connecting ideas into larger concepts, or coming up with an original creation.

One common resource for thinking about this progression from lower to higher-order thinking is Bloom’s Taxonomy, coined by a group of educators led by Benjamin Bloom in 1956 and updated in 2001. The revised taxonomy has six levels:

- Remember

- Understand

- Apply

- Analyze

- Evaluate

- Create

Another framework for thinking about HOT skills is Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, developed by Norman Webb. These four levels include:

- Recall and Reproduction

- Skills and Concepts

- Strategic Thinking

- Extended Thinking

Both Bloom’s Taxonomy and Webb’s Depth of Knowledge are helpful starting places for educators when planning complex, active learning activities. Teachers can use these frameworks to plan lessons by identifying the kind of higher-order thinking skills they’d like students to apply. Using the principles of backward design, teachers start by asking questions like what information students need to understand at the beginning of a project so that by the end, they can come up with an original creation.

What do these higher-order categories—creating, evaluating, and extended thinking—look like in the classroom? Here, we break down several types of higher-order thinking, with examples of what they each look like in practice.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is another nuanced term in education that often has different interpretations. At a basic level, critical thinking is the ability to question, interpret, and make judgments about information rather than accepting an idea or concept at face value. In general, critical thinking is something students do.

An example of critical thinking in the classroom might be having students analyze a news headline. Educator and instructional coach Dara Savage explains how she uses the FIRE method to help her students think critically about news headlines, asking students to:

- Focus and respond to the headline

- Identify a phrase or piece of the photo and write about it

- Reframe their initial response around a specific word, phrase, or section they identified

- Exchange their thoughts with a classmate, connecting the conversation to broader topics in class

The key to what Savage does here that accelerates student HOT skills comes in the “exchange” phase of their protocol. Students must have an avenue for sharing their new understandings, which allows them to analyze, synthesize, and evaluate feedback they receive from their peers.

In this way, critical thinking asks students to go beyond memorizing and understanding new information to analyze and evaluate what they’re learning. In doing so, students need to make active connections between concepts and ideas, such as comparing a new piece of information to what they know to be true from previous learning or their own lives.

Comprehension

Comprehension often appears in reading and literacy practices; however, like critical thinking, comprehension means understanding a subject’s explicit and implicit meaning. Students’ comprehension of algebra means understanding how to apply and use those same formulas to make predictions and evaluate future concepts. A step up from memorization, comprehension asks students to apply their knowledge to an evolving sense of understanding.

Unlike memorization, comprehension is an active process. For students to understand a new concept, they must extract meaning first and be able to connect it to the knowledge they already grasp. Doing so allows students to understand how new information connects to their larger understanding of themselves and their material realities.

One way of thinking about comprehension is through Marzano’s Nine Instructional strategies, a research-backed sequence to ensure rigorous learning. In this framework, building comprehension comes from helping students interact with new knowledge and helping them practice and deepen new understanding. Strategies to use at these levels include:

- Chunking content into digestible bites

- Helping students examine their reasoning

- Helping students practice skills, strategies, and processes

Metacognition

Metacognition means thinking about thinking. As a resource from Reading Rockets on higher-order thinking explains, metacognition asks students to become active participants in their learning, considering questions like: How well have I mastered this concept? What additional knowledge do I need to analyze this piece of information? What are my strengths as a learner, and Where do I need more support?

Evaluation

The Learning Center at UNC defines evaluation as “making judgments about something based on criteria and standards.” Often, evaluating something doesn’t mean students will arrive at one “correct” answer. Instead, students make a judgment and then—crucially—support that judgment with reasoning and evidence.

Questions teachers can ask students to spark evaluation include:

- Do you like, dislike, agree, or disagree with an author’s perspective or decision?

- What would you do if asked to choose a given situation?

- When faced with multiple approaches to a challenge, which approach is most effective?

To encourage stronger evaluation and not just surface-level answers, teachers should follow these questions by asking students to go deeper. How can students support their response by synthesizing evidence, critically evaluating sources, and bringing examples from their own life?

Synthesis and Analysis

Synthesis and analysis are two complementary ways to activate students’ higher-order thinking by helping them understand the connections between different pieces of knowledge or information. The Learning Center at UNC defines synthesis as: “considering individual elements together for the purpose of drawing conclusions, identifying themes, or determining common elements.” Synthesis means shifting from looking at individual parts to considering the whole instead. Analysis asks students to do the opposite: break down larger concepts into smaller pieces.

Common synthesis activities include those that ask students to:

- Generalize information and construct new understandings

- Explore relationships between different concepts

- Identify patterns and categorize information.

Analysis activities use questions that ask students to:

- Understand how different parts connect to the whole

- Deconstruct and understand various perspective

- Examine and evaluate individuals parts of a concept or problem

Inference

An inference is “a conclusion or opinion formed because of known facts or evidence.” Implicit in this definition is higher-order thinking because students take facts or evidence they comprehend and use them to create new knowledge or understanding.

Sometimes students see generating inferences as a guess or jumping to a conclusion. By breaking down the mental steps that go into making an inference, you can help students avoid this pitfall. Slow down their thinking to arrive at an understanding based on evidence and critical thinking. For example, when making an inference, students should:

- Begin by identifying relevant facts and evidence

- Consider any assumptions or biases they might hold that are impacting how they interpret facts and evidence

- Test inference to see if they hold up or if they need to revise and reconsider

How to use Higher-Order Thinking Skills in the Classroom

Educators should begin with the end in mind to teach higher-order thinking skills in the classroom. Using backward design as a process, start by asking questions such as, what kind of thinking will students need to apply to achieve success? From there, teachers can more effectively scaffold students’ lower-order thinking skills to support a deeper foundation of conceptual thinking–such as memorization and identification.

This design cycle works best with overlapping teaching methods, such as project-based, inquiry-based, and experiential learning. At PSI High, an XQ school in Sanford, Florida, students designed micromuseums to explore different facets of local history. Through this project, they applied higher-order thinking skills to analyze the needs of their community and create original, new ways of approaching local histories.

Experiential learning uses a similar approach where students learn by doing, typically in an environment outside of the traditional classroom. Successful, layered PBL activities usually incorporate experiential learning activities that activate student HOT skills. In inquiry-based learning, students approach learning like scientists, constructing knowledge rather than regurgitating it.

Each method requires students to use higher-order thinking to apply their skills and knowledge to unique, open-ended situations. Success in these methods means designing learning around key objectives and providing opportunities to assess and reflect on mastery. Below is a step-by-step walkthrough of this process.

Identify Learning Styles

Effective scaffolding involves teachers identifying how their students learn best. Higher-order thinking strategies can be adapted to support many different types of learning, but it’s essential to know the stepstones and accommodations necessary to ensure all students learn equally. Consider the neurodiversity of your classroom when planning out your objectives—how can I incorporate opportunities for visual, verbal, concrete, and abstract thinking? How much time will my students need to complete more complex thinking tasks? How will I check for student understanding?

Educator Karen Harris explains how she uses thinking inventories—or a series of essential questions—to include all learners in higher-order thinking. By posing thinking inventories at the beginning of a unit, students can think over the questions at their own pace throughout their learning and approach the essential questions through various activities before they return to the questions at the end of the project.

Define Objectives

Begin your project or lesson by explicitly defining what higher-order thinking skills students should master within the project context. Use resources like Bloom’s Taxonomy and Webb’s Depth of Knowledge to describe what kind of higher-order thinking students should be able to do—such as analyzing, synthesizing, or creating.

Clear objectives will ensure that the chosen activities align with the thinking you want to promote. Common pitfalls of higher-order thinking lessons include lessons that look good from the outside but miss the intended thinking skill. For example, students might “create” a diorama representing a scene from a book they’ve read without creating new knowledge about it. Instead, a higher-order thinking task that more effectively achieves the objective to “create” might ask students to write an original story imagining a character from the book in a new situation. But to ensure students are operating at a high level, build in time at lower levels that reinforce their comprehension by activating prior knowledge.

Select Appropriate Activities & Lessons

Meaningful and engaged learning, an important XQ Design Principal for schools, happens when students have access to authentic learning experiences. As you plan activities and lessons, consider how to create authentic learning experiences by selecting activities that connect to students’ lived experiences. How can you build lessons around real-world challenges? When students see the relevance of learning to their lives, they are more likely to feel motivated to ask more profound questions that lead to higher-order thinking.

Explore these strategies to emphasize relevance and rigor in higher-order thinking lessons:

- Choose compelling topics relevant to students’ lives, allowing them to explore diverse perspectives.

- Make local connections, including partnerships with local nonprofits and businesses.

- Create authentic projects that tackle complex, real-world problems, especially if those projects can focus on their local communities.

Assess and Reflect

Traditional assessment often asks students to demonstrate memorization of knowledge and information. While many standardized tests use multiple choice questions framed around “analyze this” or “evaluate that,” these questions are more suited for identifying comprehension rather than a student’s ability to apply HOT skills.

Assessments of higher-order thinking should focus on students’ depth of thinking and ability to apply reason. If teachers are looking to assess a student’s progress on the objectives from the beginning of the lesson, a constructed response or reflection on a project can provide a much more robust picture of a student’s HOT skill development. Summative assessments are best reserved for monitoring student progress and should aim at adjusting instruction only.

Higher-Order Thinking and XQ Learner Outcomes

Higher-order thinking supports academic achievement by moving students beyond memorization to build creative and critical thinking skills. Rather than teaching students to memorize content for the sake of a test, higher-order thinking prepares students as original thinkers and learners for life—self-directed, curious, and able to seek out and apply information to solve complex problems. That’s the goal of the XQ Learner Outcomes.

Explore these strategies for higher-order thinking in your classroom to deepen student engagement and prepare students to meet future problems creatively and confidently.

Photo at top by Chris Chandler