On the Shoulders of Giants: Algebra, Equity, and Math

This month we honor the legacy of a giant in the field of mathematics teaching and…

This month we honor the legacy of a giant in the field of mathematics teaching and the fight for educational equity for all students. Bob Moses, who founded the Algebra Project, died in July of 2021 at the age of 86.

Moses was a leader in defining mathematics as a civil right. He saw the outsized role algebra plays as a gatekeeper in determining which students move ahead academically. He knew the argument that some students just aren’t “math people” was a myth, and that all kids can and must learn mathematics. Yet, success in algebra as a course—and mastery of the skills that come along with succeeding in it—still predicts future success. Students whose schools don’t help them advance through algebra into higher-level math courses are less likely to get into college; and those who do often wind up taking costly remedial courses. These students are disproportionately kids of color and from low-income communities.

Bob Moses knew this trajectory had to change, and he spent half his life seeking to provide a better mathematics education for all students. While achieving educational equity remains a challenge 40 years after Moses started on the Algebra Project, we can further the goal by rethinking the high school experience with equity at the core—from mission and culture to teaching and learning. Our XQ learner outcomes include mastering all fundamental literacies, including math, so that students gain the skills to become truly agile with the academic core necessary to prepare for college career and life.

(Bob Moses in 2015, Susan Young, Susan Young Photography, courtesy of The Algebra Project)

Bob Moses and Algebra as a Civil Right

When Moses founded the Algebra Project in 1982, he was already an icon for his work registering Black voters in Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. He had just won a MacArthur fellowship for promoting community leadership and social change in Mississippi and was working on his doctoral degree in philosophy at Harvard when he noticed a troubling pattern at his daughter Maisha’s middle school in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Maisha had just entered eighth grade. Moses knew she was ready for algebra and didn’t want her to wait until high school to study the subject. But her teacher didn’t feel comfortable teaching it. Moses, who had taught math in New York and in Tanzania, agreed to teach algebra to Maisha and three white students who were ready for higher-level work.

As Moses looked around Maisha’s classroom, he spotted three distinct groupings of students: “Mostly, upper-middle-class white kids above grade level; a better racial mix of kids at grade level, mostly middle-class; and kids below grade level who were primarily minority students and working-class whites,” he wrote in his 2001 book Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project.

“The most urgent social issue affecting poor people and people of color is economic access. Just like voting was the key to full citizenship in the 1960s, in today’s world, economic access and full citizenship depend crucially on math and science literacy.”

– Bob Moses, The Algebra Project

Moses organized teachers and parents in Cambridge and launched the Algebra Project. Since the 1980s, the program has been used in 20 states and the District of Columbia, in nearly 200 schools, with a focus on students who aren’t given adequate opportunities to learn mathematics due to issues of race, ethnicity and class. Moses continued advocating for math education until his death in July of 2021 at 86. His daughter Maisha is now executive director of the Young People’s Project, which trains high school and college students as math literacy workers.

In his book, Moses said the Algebra Project wasn’t about school reform. He’d learned about the power of grassroots, community organizing from Ella Baker, of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He called the Algebra Project “first and foremost an organizing project,” that “draws its inspiration and methods from the organizing tradition of the civil rights movement.” Algebra might deal with abstract concepts, but Moses was interested in helping all young people feel a tangible connection to it, in order to level the playing field.

Taking Math to the People

When Moses worked with students in Cambridge in the 1980s, he saw how not all of them learn through rote instruction. Improving math education, he realized, requires new ways of reaching all learners. His Algebra Project included meaningful, engaged learning; cultivated positive relationships with young people; and also gave students a voice. (XQ has modeled much of that vision in our guiding design principles for better high schools.)

For example, Moses believed it was important for kids to bring their own experience to a math problem, talk about it in their own words—what he called “people talk”—and then apply the more academic language of math and symbols. Moses took his students to ride the subway (or T, as it’s called in metro Boston) so they could understand negative and positive integers as train stops before and after a given location. These experiential learning activities remain a feature of the Algebra Project.

At Coconut Creek High School in Broward County, Florida, teacher Johnnie Sloan said he was skeptical when he first started using the Algebra Project four years ago because “it’s not in a textbook.” But his mind has changed after trying the approach.

For example, when students graph a linear equation with a slope-intercept form, Sloan breaks them into small teams and gives each group a separate problem to solve on big sheets of chart paper. “Nobody can just sit there and let somebody do all the work because everybody has to talk,” he said. He’s also taken them on trips around the community to experience how distances work, similar to what Moses did when he rode the train with his students.

Sloan, who worked with 10th graders during the 2021-22 school year, said his students tested at the lowest levels of achievement when they started high school. Their comfort with math, and their success in mastering it, have improved now that they’re more engaged. And when he looks at the older students he taught a few years ago, he said some were getting As and Bs in the most recent school year. “Now we’re talking college,” he said. “You can see these kids are blossoming.”

Demanding Equity in Math Education

The Algebra Project treats algebra as a language, one that all students can master when they’re exposed to it gradually through the right lessons and activities. Schools and programs throughout the country have taken up some of these practices, and are trying to fill gaps in mathematics education with other techniques.

Yet, our nation’s high school students are performing below those in other developed countries. College Board tells us that less than half of all graduates are ready for college or career and a full 40 percent of 12th graders are below basic in math on the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the last one offered before the COVID pandemic. The proportions of those below basic were even higher among Black and Latino students. And no wonder when nationally, nearly one-quarter of Black students are never even offered higher-level math classes like calculus.

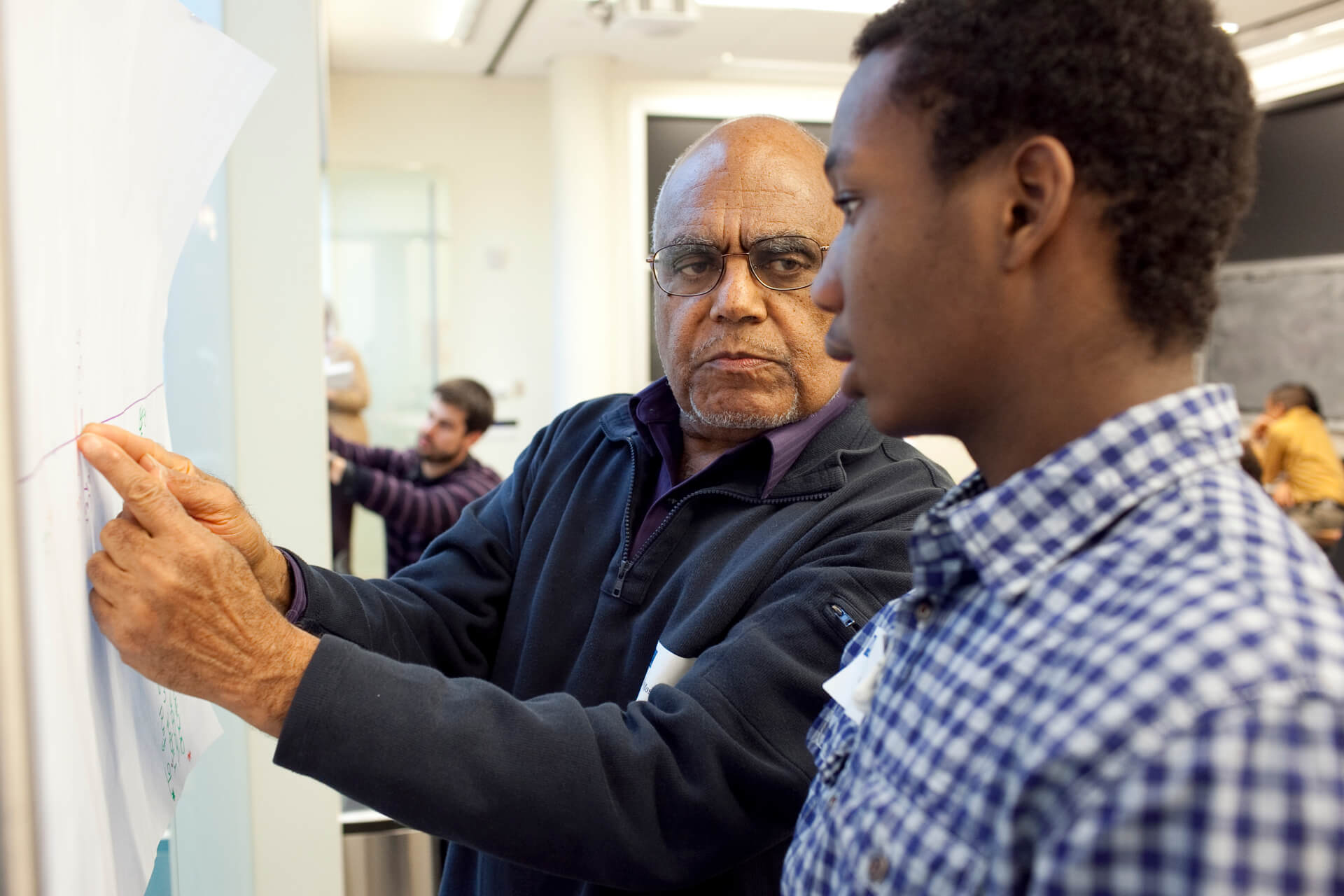

Moses with students, Math for America workshop, NYC, Nov. 2010 here and at top of page (David Lisnet, Math for America)

In Radical Equations, Moses wrote that “economic access and full citizenship depend crucially on math and science literacy.” This same belief led parents and students around the country to file lawsuits over the past two decades, seeking to force their states to provide enough funding for an equitable education. They cited schools with neglected, crumbling facilities, aging textbooks, and a lack of high-quality teachers. New York State finally complied with a 2006 court ruling at the end of 2021.

In the later years of his life, Maisha Moses said her father saw U.S. history defined by 75-year “constitutional eras,” during which the country either lurched forward or backward in terms of rights. She said he often pondered the direction of the next lurch, roughly 75 years after the Civil Rights Movement. “He urged us to think about our work in the Algebra Project, the Young People’s Project, and more broadly in quality education as a civil right, as one of the deep organizing forces that can potentially help the country to lurch forwards in this next era,” she explained.

Moses also pressed for a state and federal right to education. He spoke about this in a 2020 panel discussion with XQ’s CEO and co-founder Russlynn Ali and Jamarria Hall, a plaintiff in a case in Detroit that raised the issue of a student’s constitutional right to literacy.

Maisha Moses said her father’s views were shaped by spending more time in schools during the last decade of his life. “And the more he understood the realities of the problem on the ground and the complexities of the problem on the ground, the more he tied it to his lived experience of the Civil Rights Movement.”

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed our nation’s educational inequities even further. As communities everywhere experienced disruptions in education, Moses noted how those with the means were able to ensure their students received extra opportunities to make up for what they lost in school. In an editorial published posthumously last year, he said organizing for change has to begin with math.

“By elevating math, alongside reading and writing, as an essential literacy, we can substitute the old pre-COVID-19 normal for a new one, where students get the space they need to operate as active problem solvers and claim their place inside information-age technologies and economies.”

It was Moses doing what he’d always done: organizing for change so everyone could realize the full benefits of citizenship.

“When Bob Moses said ‘Math literacy is the key to 21st-century citizenship,’ many people weren’t sure what to think,” XQ’s CEO and Co-Founder Russlynn Ali said, at a panel discussion last October with Maisha Moses on the 60th anniversary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “Why math? What do constants, variables, and coefficients have to do with the fight for full citizenship?”

But she said people saw Moses was onto something: that focusing on math is an important lever in the larger mission of expanding access to opportunity for all.

“One of our mindsets at XQ is that we’re ‘standing on the shoulders of giants.’ Moses was one of those giants. He believed math literacy was the key to 21st-century citizenship. But we still have a long way to go. We know from the last NAEP test in math that about 11 and a half million young people from the class of 2019 probably had trouble understanding basic things like the scale on a map, or how to calculate unit pricing at the grocery store. We have to do better and achieve universal literacy in math. It’s time to give every young person the opportunity to achieve that—it’s a cause that is just as urgent as when Bob Moses said those words many decades ago.”

Russlynn Ali, XQ Institute

Continuing the Legacy

Math remains a lever in the fight for true educational equity. This month, the We the People Math Literacy for All Alliance is holding a free, online conference from July 28-30 honoring Moses’ legacy and highlighting math literacy initiatives. The Alliance is a coalition of groups including the Algebra Project and the Young People’s Project. Ben Moynihan, the Algebra Project’s interim executive director, said the event is “a call for students and teachers to be at the center, along with mathematicians, mathematics educators, researchers and community activists, in designing and implementing strategies that raise the floor of K-12 math literacy.”

“As Bob and community organizers like him have said, the people living with the problem every day must be centrally involved in designing and implementing the solutions to the problem,” said Moynihan.