How This STEM Teacher Keeps Her Students Engaged with Project and Place-Based Learning

Remote school has challenged how we create meaningful learning experiences for our students. XQ schools are using place-based and project-based learning to increase student engagement in meaningful ways.

The pandemic continues to illuminate the importance of meaningful and engaged learning, rather that’s remote, hybrid, or in-person. We’re inspired by the schools and districts leveraging this moment to rethink schools and systems for the long-term, beyond just reacting and responding in the short-term. This type of deep transformation is necessary and possible. We’ve observed that schools committed to elements of the XQ Design Principles—like a unified sense of purpose, deep knowledge of their students, strong connections in their communities, and well-developed habits of innovating to solve problems—continue to create learning experiences that are deeper and more meaningful.

Schools in the XQ network created these learning experiences and focused on bringing project-based learning to the home environment. For instance, Circulos staff created a virtual exhibit for students to showcase their work to their parents, teachers, and the broader school community. Educators at Washington Leadership Academy started integrating the arts as a way to keep students engaged in STEM learning. And, Crosstown High’s science classes filled its curriculum with rigorous place-based and project-based learning even during remote schooling.

Relating Science to the Real World through Project and Place-Based Learning

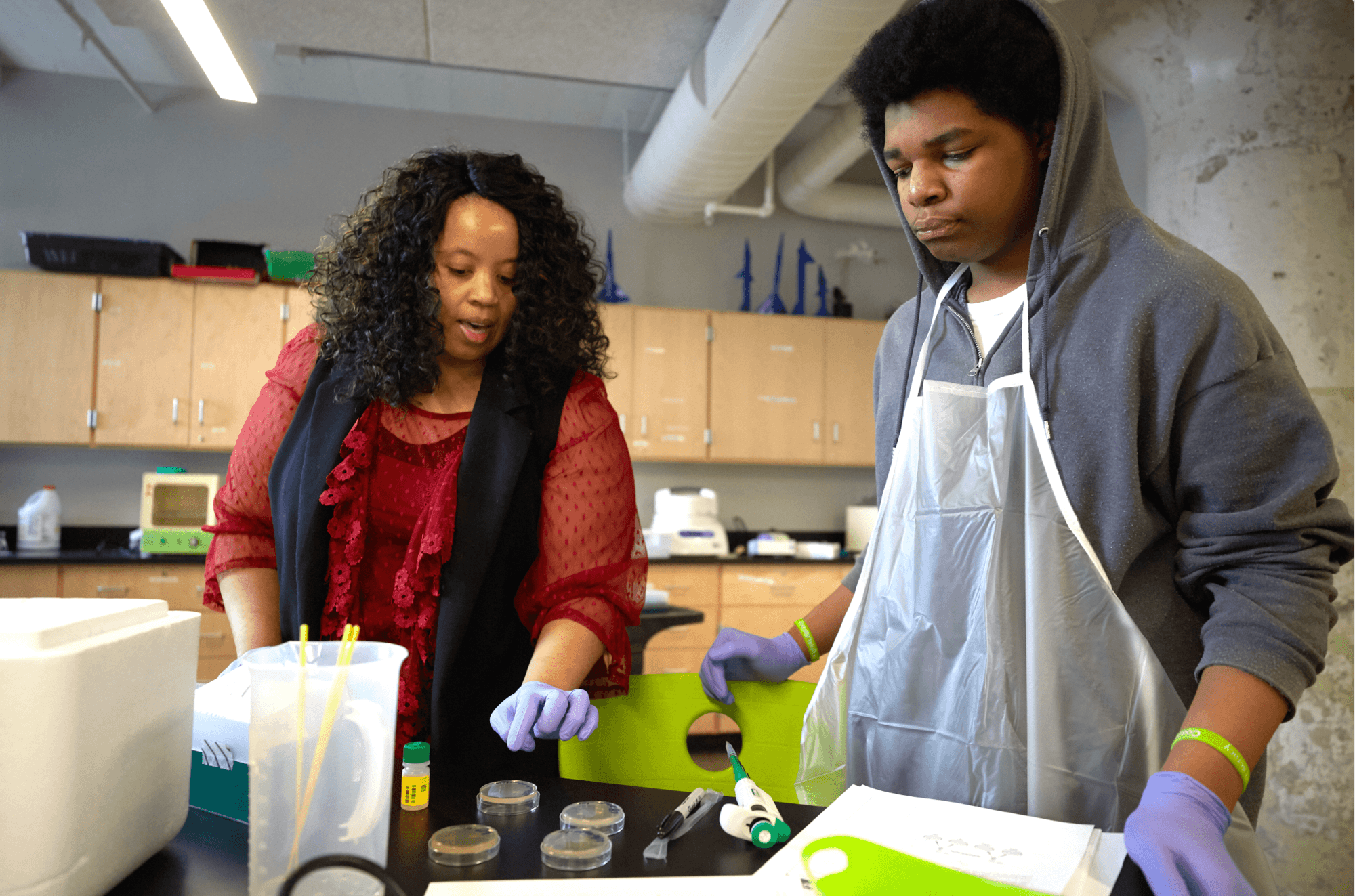

In Nikki Wallace’s environmental science class, rivers and trees and bacteria aren’t just chapters in a textbook. They’re a connection to the planet—and they’re what makes her classes come alive.

“Everything on earth is connected. That’s what I try to impress upon my students,” says Wallace. “Some people think it’s OK to dump trash ‘over there,’ or downstream. But eventually, it’ll find you. Everything is linked. That’s what my class is about.”

Wallace teaches ninth and tenth grade environmental science at Crosstown High—an XQ school in Memphis, Tenn that has centered student voice from its inception. But her project-based learning lesson plans reach far beyond the classroom. Her students explore local parks and rivers and even their own backyards, taking the lessons they’ve learned in the (virtual) classroom and applying them to real-world scenarios.

Head over to our snapshot of the school to learn more about how the school prioritizes community partnerships in its learning experiences.

In the process, students learn how their own actions can make a difference in their community and beyond.

“This class really opened my eyes,” ninth grader Christian Ryan explains. “It showed how we’re not as careful as we should be with the environment. We have to do a better job.”

Learning by Doing: What Is Project-based Learning?

Project-based learning is a hallmark of XQ’s approach to rethinking high school. When students apply their academic knowledge to meaningful, real-world projects, they see the value of their learning and are more engaged in school. XQ schools around the country—of all sizes and types—embrace project-based learning as a way for students to connect deeply with the content they’re learning in the classroom. Wallace’s class is proof of two key benefits of project-based learning: it leads students to develop new insights and sparks creativity for even the most disengaged learner.

For one of Wallace’s most popular project-based learning lessons, students pick a location in their neighborhood—a park, a creek, a schoolyard—and identify an ecological problem. That could include anything from litter to contaminated soil to invasive species. Then students work in groups to brainstorm a solution, using their creativity, knowledge, and research skills.

In some cases, they design filtration systems to keep trash out of creeks or chemicals out of the water supply; or alternative energy systems that reduce air pollution; or green roofs that can improve a building’s energy efficiency; or bat houses that can provide natural pest control, as bats eat thousands of mosquitos a day.

McKenzie Brittingham’s group came up with a unique idea to solve a litter problem: Build a trash can that works like a Venus flytrap, composting food waste as it accumulates.

“Virtual school can be boring, but in Ms. Wallace’s class we have all these projects,” says Brittingham. “She gets us to participate. And then we all feed off that energy, which makes the class better. It’s just a fun class.”

Connecting to the Community: Place-based learning

For another project in Wallace’s class, students visited Cypress Creek, a channel through northwest Memphis where several industrial manufacturers dumped chemicals until the 1960s. The class studied soil contamination, cleanup efforts, and the long-term impact on the community, including rates of cancer, birth defects, and infant mortality.

Projects like that help students see the connection between environmental science and their day-to-day lives, Wallace explains. Place-based learning links students’ academic work to the community in which they live. By venturing outside of the classroom, students broaden their perspective and gain a deeper understanding of their role in the larger community. They also see their community in the context of the wider world—what works, what doesn’t, and how they can have a positive impact.

“In order for kids to ‘get it,’ they have to see what the problems are in their own communities,” she said. “But that makes them more committed to learning, too. I tell my students, you are the ones who are going to solve these problems.”

Another project helped students learn about the flora and fauna in their immediate surroundings by identifying plants and animals they see every day. Using the iNaturalist app, students identified what lives in their backyards, local parks, and neighborhoods. That exercise helped them understand the particular ecosystems of Memphis, the pervasiveness of invasive species, and the challenges facing native wildlife.

Currently, Wallace is working with oncologists and psychologists at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis to create a high school curriculum focused on cancer. Cancer Learning in My Backyard—the title of the new project—would explore how diet, environment, behavior, and other factors contribute to cancer risks.

‘My mission is to teach science’

Science is a life-long passion of Wallace. Since she was a kid growing up in Memphis, she was either playing outside or watching PBS nature documentaries. But it wasn’t until she was a teenager that she thought she could make a career of it.

A neighbor who was a doctor, and a favorite mentor, suggested to Wallace that she enroll in a summer science camp to enhance her natural interest in the subject. Wallace was hooked and decided to devote her career to scientific research.

At the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, she majored in biochemistry and cellular and molecular biology, eventually landing a job as a researcher at a neuro-engineering lab at Georgia Institute of Technology and later at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, where she worked as a pediatric cancer researcher.

But after several years toiling in laboratories, her interest drifted toward ecology and environmental science. At age 30, she was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease that she thought might be connected to her mother’s exposure to Agent Orange while serving in the Vietnam War. Wallace found herself spending more and more time studying the links between health and the environment.

Wallace’s Transition to Teaching

Meanwhile, she was finding it increasingly difficult being one of only a few Black scientists in the laboratories she worked. The experience often left her isolated and frustrated, she said. According to the National Science Foundation, Black people represent only 2.5 percent of workers in the life sciences.

So 11 years ago, Wallace changed careers and became a teacher. She’s been at Crosstown since it opened four years ago.

“My mission is to teach science, and encourage kids, especially kids of color, to pursue careers in science,” Wallace explains. “We need more people of color in the sciences. We bring a different perspective. … Let us be at the table. If there’s enough of us at the party, maybe we can beat the door down.”

The Key to Keeping Students Engaged: Make science fun

Wallace’s enthusiasm for science has made a big impression on her students. Many said they had no interest in the topic until Wallace’s class when, through project and place-based learning, they suddenly saw how science impacts their community and relates to their lives.

“I love her class,” said Jonna-Richie Ingram, a ninth grader who spent last semester planting lettuce, working in a community garden, picking up trash, and doing other ecology-focused projects for Wallace’s class.

Wallace’s focus on place-based, project-based learning makes class engaging and rewarding for her students, and put them on a path for success. It’s sparked a love of science and an interest in the environment—in their own backyard and the world beyond, her students say.

“Ms. Wallace explains things really well and is always there to help us,” Jonna-Richie said. “And she makes sure we have fun with it.”