Why the School System Needs to Change, and How

Take a moment to think back to your high school years. Picture the school, the classroom, and the things you did there. Odds are, you recall rows of desks, a teacher lecturing at the front, textbooks, tests with paper and pencil, and a bell that rang every 50 minutes so you could sprint down the hall to your next class. You repeated it, again and again, each semester for four years until you were handed a diploma—a piece of paper that said you were ready for whatever came next.

Whether high school was five years or 50 years ago for you, this description is likely familiar. It is the time-based model for secondary learning that first took hold as the U.S. shifted from an agrarian to an industrial society at the start of the 20th century. And it’s a model that most high school students still experience today.

The world keeps changing yet this century-old structure persists—threatening our country’s competitive edge in the world while contributing to declining economic mobility. It’s also not a style of learning that matches our 21st-century lives. That’s why it’s no surprise that many high school students feel increasingly disengaged in schools that are disconnected from their current and future lives.

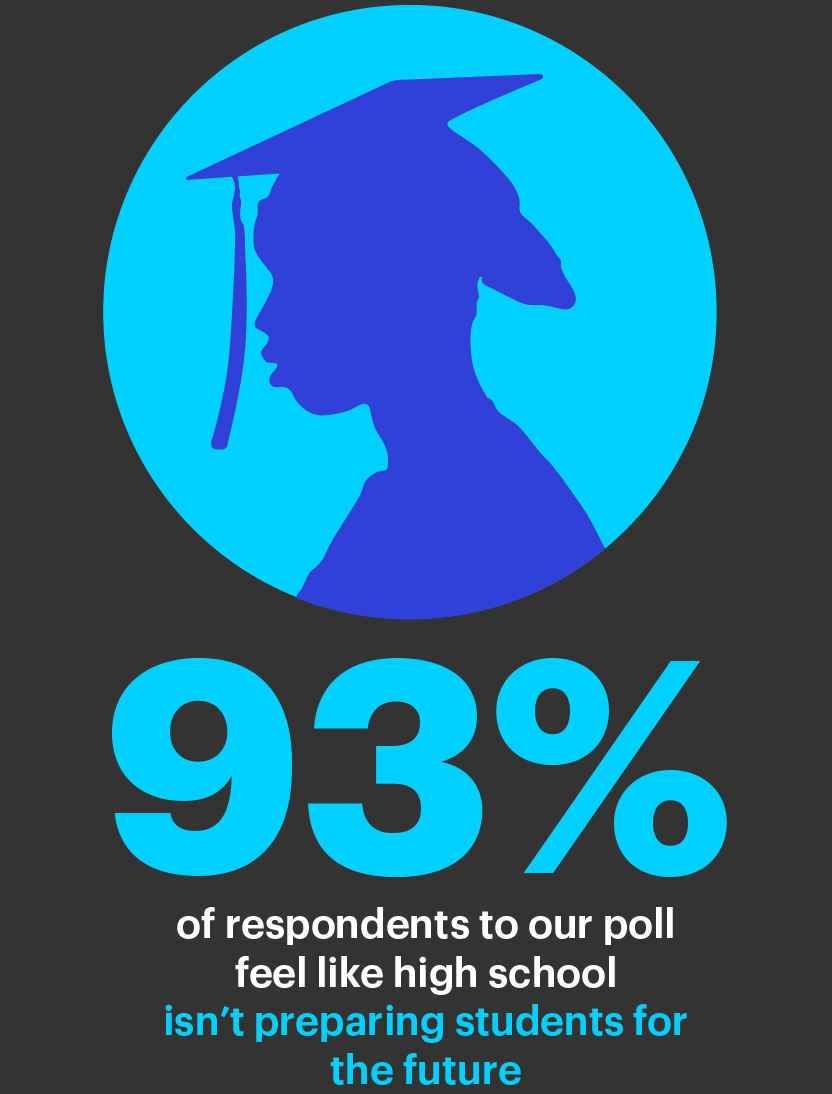

We at XQ believe it’s time to rethink high school so students are more engaged and prepared for whatever their future holds, whether that’s college, work, an apprenticeship, public service, or the military. We invited our community to weigh in through an informal poll and here is what they told us:

Out of more than 300 participants polled, the vast majority—93 percent—said they didn’t think high schools are fully preparing students to succeed in the future.

Today’s high school students also have tremendous academic needs, based on how they were doing in middle school. Math and reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), commonly called “The Nation’s Report Card,” were at their lowest levels in decades. On NAEP’s Long Term Trend assessment results for 13-year-olds in the 2022-23 school year, average scores declined 7 points in reading and 14 points in mathematics compared to a decade ago. Scores had been trending downward even before the pandemic and struggling students were hit especially hard. In related NAEP news, more students were performing below basic on the 2022 assessments of 8th gradres—38 percent in math and 37 percent in reading—which means they didn’t even master enough content to reach the lowest score on the tests.

We have less data on high school students because the most recent national assessment of 12th graders was in 2009. But the numbers were already sliding: a higher percentage of 12th-grade students performed below NAEP basic in both mathematics and reading in 2019 compared to four years earlier. And 41 percent of 12th graders were below basic that year in science.

Based on the recent middle school results, far too many of today’s high school students are unprepared academically. That puts them at a profound disadvantage both for college and career. A 2022 survey from Manpower Group found that 75 percent of companies report talent shortages and difficulty finding in-demand skills like creativity and problem-solving. Those are skills that should be further developed during the teenage years.

For our students, high school should be—and can be—so much more. Rethinking high school means understanding how the typical U.S. high school developed, why it’s outdated, and how we can create a new and better architecture for learning that can exist in any community and serve all learners well.

What is the Carnegie Unit and how does it impact high schools?

“The Carnegie Unit was developed in 1906 as a measure of the amount of time a student has studied a subject. For example, a total of 120 hours in one subject—meeting four or five times a week for 40 to 60 minutes, for 36 to 40 weeks each year—earns the student one ‘unit’ of high school credit. Fourteen units were deemed to constitute the minimum amount of preparation that could be interpreted as ‘four years of academic or high school preparation.’”

For more than a century, learning in America has been tethered to a bell. Launched in 1906, time-based education was a response to the previous century’s schoolhouses dotting the country. With their narrow scope and uneven quality, the earlier inception of public schools could not prepare a new generation to participate in a growing democracy and changing economy. To solve the problem, the educator Charles Eliot and the steel magnate Andrew Carnegie (with the aid of his Foundation) designed a new education system perfectly suited to the industrial boom.

At that time, American high schools—even with their deep flaws—were the vanguard of public education. In fact, as Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz wrote in their seminal 2010 book “The Race Between Education and Technology,” universal secondary schooling is both a modern and distinctly American idea. At a time when most countries limited access to secondary education, a system of public high schools, free to all, was itself an innovation that helped place the U.S. far above other developed nations, both economically and socially. Even by the middle of the 20th century, they note, most other nations, including wealthy ones, “educated only those who could personally afford to attend school. The United States was different.” This isn’t to say that the system ever worked for all kids—it certainly did not, and does not, equitably serve all students—but simply that the U.S. was at the vanguard of putting into practice the radical idea of free secondary education for all.

To achieve the vision for universality, a second innovation, the Carnegie Unit, was necessary. At the dawn of the 20th century, the Carnegie Unit was a truly transformative idea. It created a way to standardize education across a decentralized system of schools by using time as a proxy for learning to determine how students earn credit for completing a course of study. Once a student studied a subject for a set amount of time, they earned one unit of course credit. Enough course credits and they could graduate from high school—any high school, whether it was in a large city or a rural county. Even though every state had its own standards and curricula, the country finally had a consistent approach to secondary education they could all implement.

While the Carnegie Unit did little to address disparities in resources and quality of instruction, it established a common framework that enabled high schools to share information about their students with institutions of higher education, employers, and each other. In short, seat time became the architecture for the U.S. system of secondary learning.

High schools were designed around it: learning was separated into distinct courses, credit on transcripts was earned upon the completion of a certain number of hours in the course, and bells divided the day into course periods.

More than 115 years later, American students have the same “seat time” requirement of about 50 minutes per class, five days per week, for six courses per year, across four years. Carnegie Units (120 total) remain the currency of high school education. But there’s growing recognition—even at the Carnegie Foundation—that this time-based system isn’t flexible enough for students or teachers.

“Since the Carnegie unit was introduced in 1906, we have learned an enormous amount about how human beings learn. Neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and the learning sciences have taught us we learn through immersive experience, by solving real problems, in apprenticeships, from experts, and from our mentors and peers. And we learn at highly variable rates, depending on the individual and the subject of study. We know we do not learn based on the number of minutes spent sitting at a desk or logged onto a digital platform. The nation’s goal should be to build a truly competency-based educational sector, where rich, engaging learning happens everywhere, and young people build the skills we know they need for success in school, work, and life.”

– Carnegie Foundation President Tim Knowles

How the Carnegie Unit and our school system fails students

The conflation of time and learning is problematic for a number of reasons. The Carnegie Unit gives everyone—teachers, students, families, post-secondary institutions, employers, and more—an efficient and orderly way to organize high school education. The downside is student transcripts that mainly track time spent learning, not the specifics of what students know and are able to do.

This system ignores much of what we know from rigorous scientific research on how students learn—particularly that students learn different topics at different paces and that sitting in a classroom for a year does not guarantee learning. This helps to explain why many students need to retake courses when they enter college; up to 65 percent of community college students take at least one remedial course. Also, conflating time and learning has failed to create enough opportunities for many students, including tremendous numbers of our most marginalized and vulnerable students, as demonstrated in persistent achievement gaps in math and other subject areas.

Today, most U.S. high schools remain woefully out of touch with the world and the needs of the millions of students they serve. For these students, their day-to-day experiences appear largely disconnected from their lives, with somewhat predictable results: higher levels of anxiety and stress, mental health challenges, and more students disengaging from school.

Students worried that their high schools are not preparing them for the future are not wrong. Economists predict that, by 2025, 97 million new jobs will emerge globally, even as 85 million other jobs will be displaced, most of them low-skill, low-wage positions predominantly filled by women, people of color, and workers without college degrees. And the skills employers are looking for—analytic thinking and innovation, complex problem solving, and entrepreneurship—are the same skills our current system is ill-equipped to develop in our children.

A 2021 report from McKinsey & Company on the future of work after COVID-19 showed how jobs performed by humans are becoming increasingly automated. The pandemic accelerated this shift: the report found that up to 25 percent more workers than previously estimated may need to switch occupations. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics identified 20 occupations with the highest projected percent growth of employment between 2021 and 2031: they include data scientists, information security analysts, web developers, solar photovoltaic installers, and physician assistants.

Many of those jobs require postsecondary education. But a significant number of high school students will graduate and immediately enter the workforce. A 2020 report from the National Center for Education Statistics found a third of all high school graduates are not going straight to a two- or four-year college. This appears to be on the rise as a result of the COVID pandemic and the rising costs of college. Those students, in particular, will need to graduate with work-ready skills.

The disconnect between K-12 schools and the lived realities of today’s world has a very real impact on the long-term life opportunities of our students, particularly students of color and students living in under-resourced communities. Generation to generation, we have witnessed declining economic mobility since the 1940s. Troubling wealth gaps continue to grow both nationally and in individual communities.

The recognition of these structural flaws is not new. People have been critiquing the use of time as a primary measure of learning since at least the 1960s. According to Education Week, in 2012 The New America Foundation released a report arguing that time-based credit had become less useful for the rising number of students taking online classes and attending college part-time. Author Amy Laitinen wrote:

“If the U.S. is to reclaim its position as the most-educated nation in the world, federal policy needs to shift from paying for and valuing time to paying for and valuing learning. In an era when college degrees are simultaneously becoming more important and more expensive, students and taxpayers can no longer afford to pay for time and little or no evidence of learning.”

In a 2015 opinion piece for Inside Higher Ed, Arthur Levine, president emeritus of Teachers College at Columbia University, wrote that “states need to move consciously and systematically to the information economy’s emerging and increasingly dominant model of education, which will prevail in the future. The Carnegie Unit will pass into history.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has explored mastery-based and other non-time-based credit systems, and states like New Hampshire have piloted mastery systems. The topic of seat time has even landed in mainstream media. In late 2022, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona told Jon Stewart, “students are sitting in our high schools the same way that they did a hundred years ago, when we have internship opportunities, we have career pathways that can be explored in 9th grade.”

So why does a model for secondary learning so out of sync with today’s needs persist in the face of calls for change? The answer lies, in part, in the fact that seat time is so hardwired into the structure of secondary education that vestiges of the Carnegie Unit will remain until a new architecture for learning replaces it.

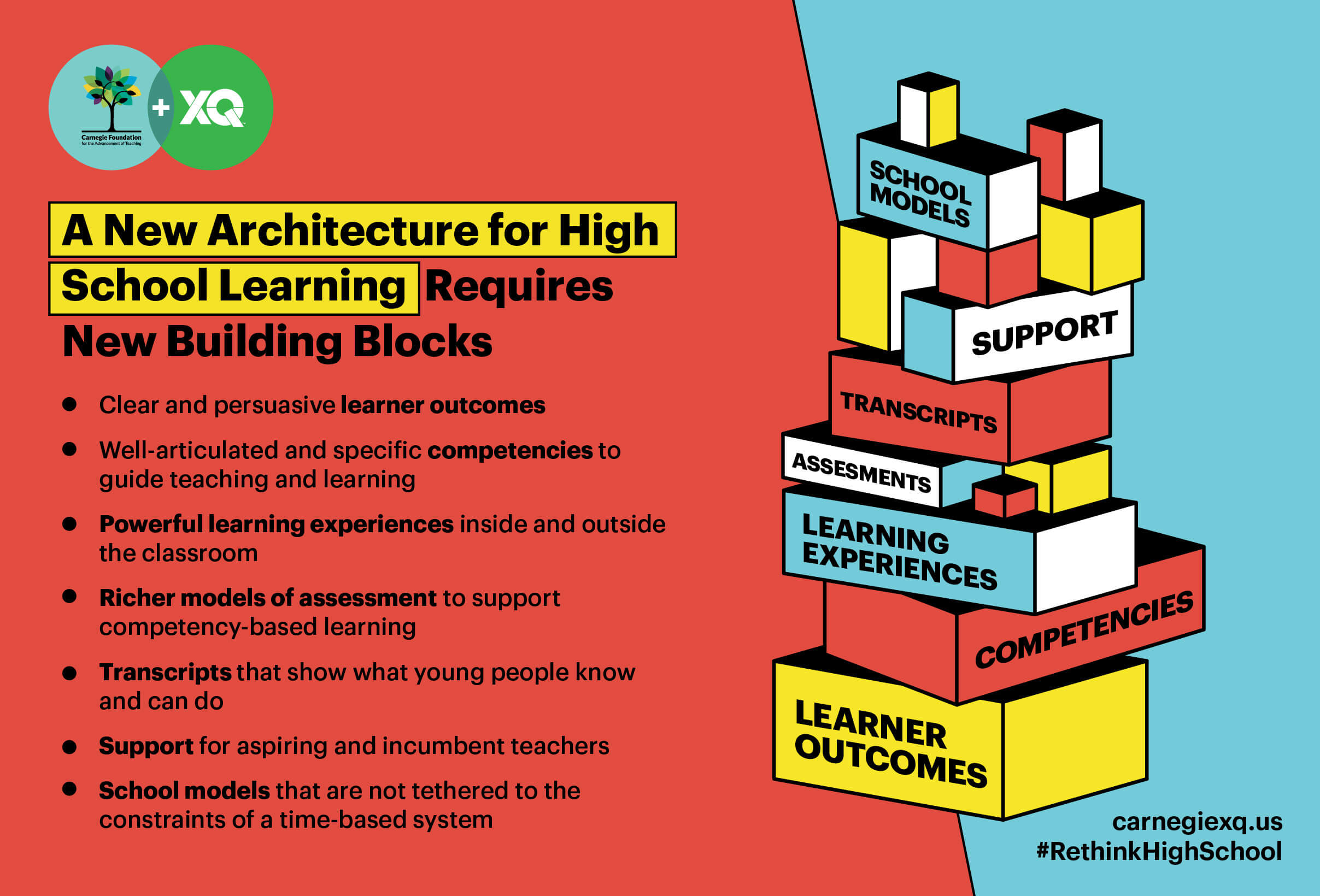

“If we’re going to rethink the system, and design a new architecture, we need new building blocks. This starts with identifying the knowledge, skills, and attributes that young people need to be prepared for life after high school, to navigate the world of work and careers that are constantly in flux, to become strong contributors and problem-solvers, and to lead fulfilling and meaningful lives.”

– Russlynn Ali, CEO and Co-Founder, XQ Institute

What would a high school education without “seat time” look like?

If we’re going to rethink the system, and design a new architecture, we need new building blocks. This starts with identifying the knowledge, skills, and attributes that young people need to be prepared for life after high school, to navigate the world of work and careers that are constantly in flux, to become strong contributors and problem-solvers, and to lead fulfilling and meaningful lives.

We call these the XQ Learner Outcomes:

- Holders of foundational knowledge—Curious people who are knowledgeable about the world. Its history and culture. Its sciences and underlying mathematics. Its biology and cultural currency. Engaged participants who are key to creating a more just and functional democracy—who participate fully in all America has to offer.

- Masters of fundamental literacies—Building the academic core necessary to prepare for college, career, and life.

- Original thinkers for an uncertain world—Sense-makers—dealing with conflicting knowledge. Generative thinkers—creating many ideas in ambiguous and new situations. Creative thinkers—reframing, imagining, and seeing problems from different perspectives.

- Generous collaborators for tough problems—Self-aware team members who bring their strengths. Talent-seekers who find the expertise of others. Essential co-creators—because of what they bring, and how they show up. Inquisitive world citizens who seek out—and respect—diversity and diverse points of view.

- Learners for life—Self-driven, self-directed. Curious learners—about themselves, and the world. Inventors of their own learning paths, careers, and lives.

Working with some of the best minds in the country and building on the best research, XQ developed these Learner Outcomes to be profoundly student-focused in ways that drive system change. What matters most is how these learner outcomes actually translate into practice—into exciting and innovative teaching and learning.

Of course, a broad call for change is just the first step in a long journey. Transforming a century-old, deeply ingrained system is a complex, difficult challenge. Among other things, it can be hard to settle on where to start.

We are convinced that the change must start with a new set of building blocks that together form the foundation of the new educational architecture we need.

Establishing the new architecture will take all of us: educators, system leaders, curriculum makers, policymakers, researchers, higher education and workforce leaders, families, and students themselves.

This isn’t a far-fetched aspiration for the future. In 2016, the Aurora Institute released a report called, Moving from Seat-Time to Competency-Based Credits in State Policy. It noted that the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching had identified 42 states with at least some flexibility for school districts to base academic credit on mastery rather than just seat time. Aurora’s CompetencyWorks map showed the progression of states in advancing policies that enable and scale competency-based education (CBE), from no state policies to advanced policy frameworks.

U.S. News & World Report wrote about the Huntley Community School District, northeast of Chicago, where high school students “move freely between classes, spending more time in the ones where they need more help. Teachers work with students to develop the skills it takes to know how they learn best and how to organize their time.” The article also noted that it’s hard to measure the exact academic impact of CBE, because it’s often implemented with other changes, and different schools use it in different ways.

Meanwhile, schools themselves are changing as a growing number of communities explore and implement models that bring the core elements of effective high school design together in new ways. XQ’s research-based Design Principles articulate those elements:

- Strong mission and culture—A clear set of school values that unify stakeholders around a common purpose.

- Meaningful, engaged learning—Interdisciplinary and engaging strategies that help students develop content knowledge and complex skills.

- Caring, trusting relationships—Personal connections between students and adults, and between students and their peers, to help them develop holistically.

- Youth voice and choice—Authentic, ample opportunities for students to build autonomy, develop agency, and develop their identities.

- Smart use of time, space, and tech—Nontraditional approaches to when, where, and how students learn.

- Community partnerships—Connections that open up real-world learning opportunities for students to gain valuable experiences that help them envision life beyond high school.

How to make the school day more engaging

What does learning look like when schools don’t have to stick to the traditional school day? At Purdue Polytechnic High Schools (PPHS), a network of three campuses in and near Indianapolis, Indiana, it would be hard to find two students with the exact same schedule. PPHS does away with the traditional high school structure. Students opt into different classes and projects every eight weeks.

“The idea that learning needs to be time-bound, or that every student learns in the same way in increments and goes from class to class is antiquated, and doesn’t really serve students well.”

– Keeanna Warren, Chief Executive Officer, PPHS

PPHS has had impressive success since opening in the fall of 2017 as an XQ school with the goal of sending more underrepresented students to Purdue University. Among its class of 2022, 39 students gained admission to Purdue University and 34 enrolled, most of whom were students of color. That’s more than twice the average number of Indianapolis high school graduates who enrolled at the university between 2016 and 2020 (15 a year), before PPHS graduated its first group of students.

Students at PPHS also had higher proficiency rates on state assessments for Black students, Latino students, students from low-income families, and students who qualify for special education services compared with similar groups districtwide and statewide.

In Michigan, another XQ school, Grand Rapids Public Museum School (GRPMS) has found innovative ways to create a more flexible learning environment for its students. District requirements mean the school still has a six-period bell schedule, but teachers alternate between classrooms, co-teach in core subject areas, and center their curriculum on project– and place–based learning experiences.

With the school nestled in downtown Grand Rapids, students are within a short walking distance of dozens of community partners, institutions, and local businesses. Learning happens in flexible spaces, outside with the community, and in dual enrollment courses at local colleges near their high school.

In addition, the GRPMS team created a “Flex Friday” system that allows students to participate in a more self-directed learning experience. During Flex Fridays, students are able to sign up for passion projects, workshops to learn new skills, and academic or extracurricular clubs. Teachers have also built in tutoring and academic sessions so students can receive additional support in subjects where they need more help or are looking to excel in their mastery. The structure allows students to build a routine that supports their individual learning goals and helps teachers offer a personalized learning experience.

GRPMS Principal Chris Hanks said the biggest hurdle to the school’s innovative design was managing so much student movement. Spreadsheets turned out to be a mess. However, the school’s science teacher, Ben Hoff, created an in-house app to resolve this. Students are prompted in advance to schedule their days, and then teachers are able to review and manage student attendance more easily. Over the past few years, they have slowly added new features to support their dynamic needs.

The school’s approach is already leading to impressive outcomes. Its first graduating class in 2022 had double the combined proficiency rate across all state assessments compared with students in 23 “similar high schools” identified by the Michigan Department of Education.

While the Grand Rapids Public Museum School is still tethered to the district’s requirements of seat time credentialing, both GRPMS and PPHS show how innovation can be achieved even as educators work to build a better system to support future learning.

Various states and districts are encouraging schools to create innovative schedules. In Indiana, schools can request waivers from state mandates. New Hampshire and Oregon are among states moving to give credit based on factors other than seat time, according to the Aurora Institute. Some districts have created innovation zones through agreements with their unions. In Boston, pilot schools have flexibility around hiring, budget, bell schedule, and curriculum. In New York City, the union contract allows school-based options if most teachers agree to a different schedule.

Badging is another way schools can document student learning through mastery of different competencies within a subject. Badges can be used in place of, or as complements to, grades, transcripts, or standardized tests.

For a comparison, think of scouting, where participants earn merit badges for activities ranging from animal science to salesmanship as they progress along a defined pathway of achievement. In schools, the typical A-F letter grades operate somewhat like low-quality badges, because they signal a student’s progress. But they’re too broad to communicate anything about actual skills or knowledge.

By certifying learning in smaller units, badges allow students to move on from what they know and focus on what they still need to learn rather than sitting through a generic, standard scope and sequence. This is particularly important because some classes with high failure rates, such as Algebra I, become barriers to achieving college readiness—even for students who ace 90 percent of algebra content. To this end, XQ is experimenting with partners in three states to create a series of math badges that address precisely this issue. We are working with Idaho, Illinois, and Kentucky to map out how badging infrastructure and partnerships need to work.

That’s why we say high school transformation is not only necessary and possible, but underway in schools and districts across the country—and the outcomes are impressive. Schools need more freedom for these models to replicate, and to take learning in a powerful direction that meets the needs of 21st-century students.

“There is a consistent message coming from many corners of the globe—from national leaders, policymakers, and places in the United States as diverse as Dallas, Phoenix, Tulsa, and Navajo Nation. The message is coming from employers, from educators, parents, and young people themselves. The message is clear. It is time to transform secondary school. It is past time. We cannot continue to educate young people in schools designed for an economy that no longer exists. We need schools designed to make students world-ready.”

Tim Knowles, Carnegie Foundation President

A new educational architecture

It’s time to initiate a significant shift away from time-bound conceptions of what knowledge is and how it’s acquired to a new system—where engaging and effective learning can happen anywhere, with learning that’s well-validated, outcomes-based, and better-matched to the full range of knowledge, skills, and capacities students need to thrive in the 21st century.

In 2022, Carnegie Foundation and XQ announced a partnership to catalyze and co-construct a new educational “architecture” to support high school transformation. This architecture will liberate learning from the confines of a time-based system and build outcomes-based educational systems—all fueled by the latest research in neuroscience and learning sciences—to prepare young people for all the future has to offer.

The goal is to create more authentic and engaging learning once subjects like biology, algebra, social studies, and English are no longer limited to discrete 50-minute blocks of time. Teachers can create interdisciplinary courses and collaborate with community partners so students can see how these subjects show up in everyday life—for example, by using geometry to solve a transportation problem, or chemistry to figure out ways of reducing pollution in a local stream.

Tom Vander Ark, CEO and co-founder of Getting Smart, acknowledged the crucial role the Carnegie Unit has played historically, but he believes it is too rigid to enable the type of learning students need now and in the future. “The Carnegie Unit yielded the efficiency of standardization in education as the shipping container did for logistics,” he explained. It defined degree requirements, provided some transferability, and drove resource allocation, staffing and licensure. But this standardization also blocked integration, reduced personalization, and inhibited a more meaningful mastery of subjects.

Vander Ark sees a future where high school courses of defined or estimated length remain a “container” for learning experiences to facilitate resource allocation. But they’ll be very different from the classes of today. “They will be accompanied by workshops, projects, internships, and independent study activities,” he predicted. “Learners will build customized schedules to fit their life and interests. These constructs for organizing learner experience will facilitate multiple unbundled opportunities for learners to demonstrate growth.”

“Progress will increasingly be marked by digital credentials signifying demonstrated and verifiable mastery of competencies. Credential clusters and other forms of evidence will be curated in lifelong learner records which will be permissioned to relevant parties to facilitate talent transactions. Permissioned employers and learning institutions will pull customized data extracts from learner records. Learners will receive inbound offers instead of applying for dozens of individual positions.”

– Tom Vander Ark, CEO and co-founder of Getting Smart

To stimulate the development of learning experiences like this, Carnegie and XQ have launched a strategic effort to produce and test a collection of powerful curricular materials, which we call CF+XQ Learning Experiences (LXs). Each module of curriculum will engage young people in learning that is project-based, high-interest, authentic, and rigorous. And unlike current domain-specific curricula, LXs will be multi-dimensional, intentionally building students’ academic content knowledge and their academic, cognitive, and social-emotional competencies at the same time.

Using the XQ Competencies, a teacher might develop an LX (or choose an existing one) in which students carry out a project with required academic content—on cell division, for example, or the Harlem Renaissance—while also developing skills in logical thinking and persuasive communication.

The typical LX will last three to six weeks—long enough to accommodate the arc of an authentic project and short enough to allow a variety of experiences across a coherent high school course. This duration also allows for learning beyond the conventional classroom and for student voice and autonomy, both essential for adolescent learners. Modular in format, LXs will be readily available to any educator who wants to try them, combine them into longer experiences or full courses, share them with colleagues, or even author them.

XQ and Carnegie are collaborating with innovative curriculum makers to test the LX format and produce an initial collection of exemplary LXs. The goal is to put an accessible and powerful form of student learning within reach of high school teachers and students everywhere. These will be the learning experiences that young people need to thrive today and in the future. They are student-centered, increase student engagement and motivation, and build productive perseverance in learning and academic identity.

The future of high school is now

High school is the last stop before students enter the real world of college, career, and adulthood. It’s an important time for adolescents—whose brains are still growing rapidly—to develop both academically and socially.

Think of how an exciting science project can spark a teen’s lifelong interest in biology. Or about a student who becomes fascinated by data science when their social studies course partners with a local housing organization and they see how poverty is linked to local housing patterns. Or the student who says “I’m not a math person,” but who discovers they can learn algebra if they’re allowed to master different elements of it at their own pace—with a teacher who understands their strengths and weaknesses. Another student could develop a love for local history and civics through an internship in local government.

There are amazing high schools throughout the U.S. committed to giving all learners a chance to explore their full potential through innovative learning experiences. But they’re not the norm. Public education in the U.S. remains rife with inequities. We see persistent achievement gaps between students of different races and income levels. Too many students are ill-prepared for college and careers. And too many students were dissatisfied with school even before the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2017, YouthTruth released a survey finding only one out of three middle and high school students rated their school culture positively.

We have to do better. Today’s high school students will eventually be our co-workers, business owners, doctors, spiritual and community leaders, and teachers educating the next generation. By equipping learners with the knowledge, skills, and confidence to succeed in an ever-changing world, high school can prepare all students to meet and shape the future. But only if we rethink high school and design a new architecture for learning that meets the needs of the 21st century.

______________________

Learn more about how to make change in classrooms now. Sign up for the XQ Xtra, a bimonthly newsletter for the high school educational community.

For more on how to change the structure of high school, read these articles:

- The Head of the Carnegie Foundation Wants to Ditch the Carnegie Unit. Here’s Why

- The Carnegie Unit: A Century-Old Standard in a Changing Education Landscape

- The High School Credit-Hour: A Timeline of the Carnegie Unit

- Let’s Bid Farewell to the Carnegie Unit

- Redefining Student Success with the XQ Competencies

Sign up for our newsletter

Get the latest educator insights and practical classroom tips every other week, direct from the XQ community

Follow us to #RethinkHighSchool