Teen Activists on Elections, Civic Life, and Grassroots Organizing

Between the pandemic, presidential election, and economic downturn—2020 has been a tumultuous year for everyone. But some high school students have taken matters into their own hands: by hitting the campaign trail.

Between the pandemic, presidential election, and economic downturn—2020 has been a tumultuous year for everyone. But some high school students have taken matters into their own hands: by hitting the campaign trail.

Learning through community action

“I firmly believe that if you don’t like the way something is being handled, you have to work to change it,” said Andres Medina, a 12th grader at Círculos, an XQ school in Santa Ana Unified School District in Southern California. “You can’t just sit by and do nothing.”

Andres is among the thousands of high school students nationwide who spent the past few months calling voters, talking to public officials, learning their rights, and trying to make a change in their communities.

For Andres, the turning point was last spring, when he saw that his community had one of the highest COVID-19 rates in the region. Unsatisfied with the response of local political leaders, Andres decided to get involved.

After researching the issues and candidates, he joined the campaign staff of a local city councilman who was running for Orange County Board of Supervisors. The candidate’s platform centered on health care, affordable housing, and other initiatives to help the county’s low-income residents cope with the pandemic.

Throughout the summer and fall, Andres talked to voters, worked on phone banks, analyzed voter trends and data, translated campaign materials into Spanish, and collaborated with his fellow campaign staffers on strategy and policies.

His candidate ended up losing, but Andres learned some valuable lessons about the political process. Namely, he learned the importance of compromise and consensus, and how a skilled politician can reach agreements with their opponents to benefit all constituents.

He also learned about voter disenfranchisement. He was especially struck at how voters who are low-income, not fluent in English, or not well educated can become disconnected from the democratic process—and so their voices are not heard by political leaders.

“It made me realize how important education is,” he said.

Beyond petitions and protests

This was not Andres’s first foray into politics. His interest in civic life started with the surprise outcome of the 2016 presidential election, the aftermath of which left him and millions of others reeling.

“I remember thinking, yes, we can protest and sign petitions demanding change,” he said. “But I realized that at the end of the day, to create real change, it helps to be in a position of power. So I decided to get involved.”

He co-founded the Santa Ana chapter of High School Democrats of America, where he researched and helped craft endorsements on a wide variety of local, state, and national issues.

In 2019, he was appointed to the Santa Ana Youth Commission, where he worked with his fellow commissioners to offer free SAT tests and SAT preparation classes for low-income students in Santa Ana.

That year he also won a grant from the Dragon Kim Foundation to start a civics camp for 3rd graders to 8th graders in Santa Ana. About 40 students participated in the 3-week summer program, where they learned about the branches of the federal government; how to debate; and how to write—and pass—legislation.

“It’s so important for young people to get involved. Politics and government have more impact on us than most people realize,” he said. “And until we realize that, nothing will change.”

Andres’s political involvement is a natural fit at Círculos, where project-based learning and community engagement center all aspects of a student’s education. Andres’s work is also a great example of the XQ Knowledge Modules and Learner Goals in action, taking classroom lessons and applying them to the real world in a way that benefits the community.

He’s not the only student at Circulos who’s politically engaged. His classmate Alexis Benitez serves as a student ambassador on the Santa Ana school board, providing important updates and insights to school board members and the public about issues that affect students.

Working the polls

Across the country, students have volunteered in the democratic process this election year. A nonprofit called Poll Hero recruited more than 37,000 young people to be poll workers throughout the country, monitoring polling places, helping voters understand their rights, and providing other vital services to keep elections running smoothly.

Many states allow high school students to serve as poll workers, even if they’re not eligible to vote.

Voting eligibility was the topic in many states, cities, and school district races. In California, a statewide initiative, Proposition 18, would have given 17-year-olds the right to vote in primaries if they were going to be 18 by the general election. The measure lost, but thousands of high school students around the state campaigned for it: making calls and knocking on doors to persuade voters.

More than a dozen states and the District of Columbia, which already allow 17-year-olds to vote in primaries. Several cities around the country considered similar initiatives on their Nov. 3 ballots, including Oakland, where voters overwhelmingly agreed to let 16- and 17-year-olds vote in school board elections.

Fighting for change in Iowa

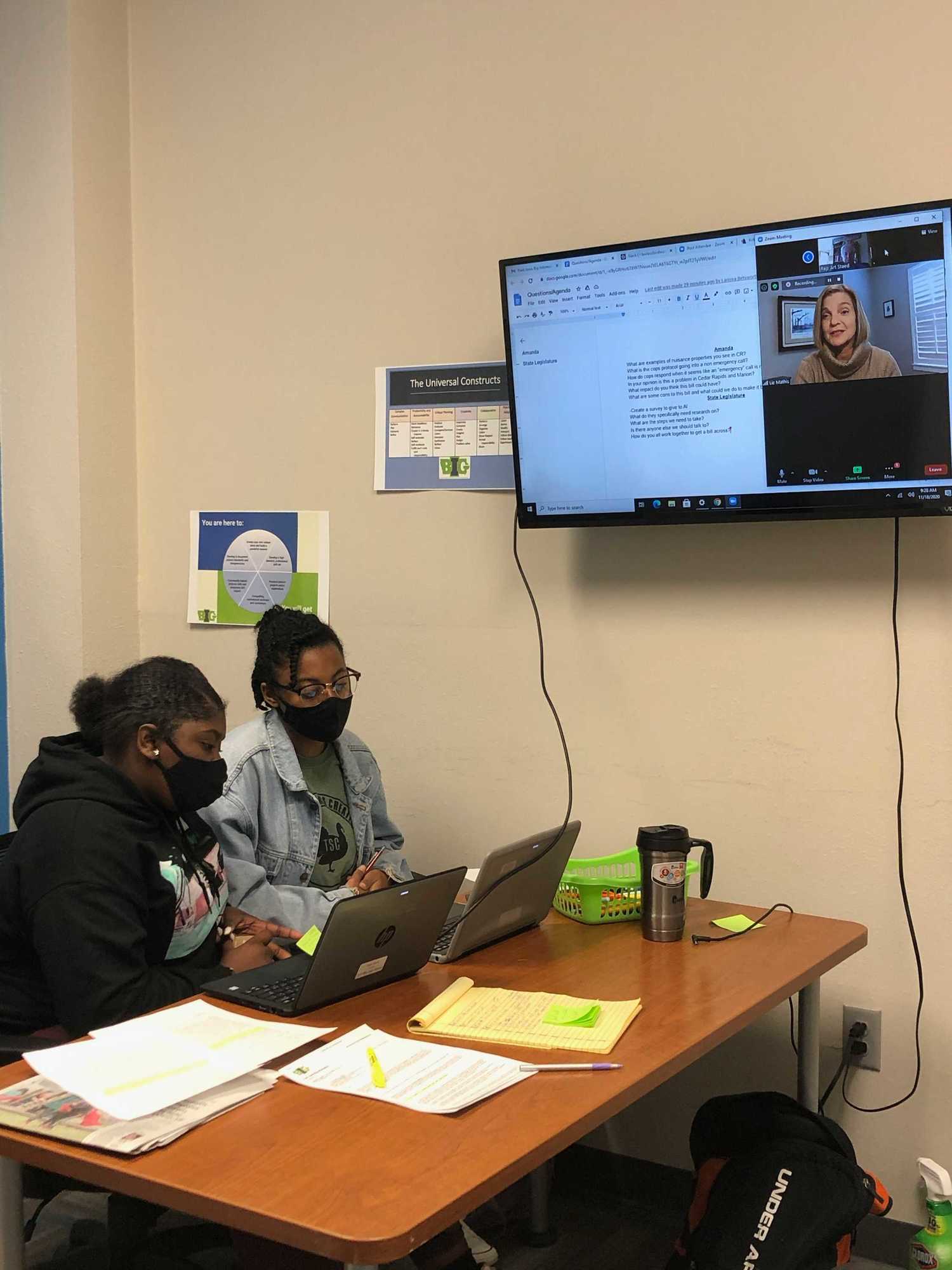

Students at Iowa BIG, an XQ school in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, undertook a different kind of political project: fighting for a state law that would make it a hate crime to call police on people of color when they’re not committing a crime. Other jurisdictions around the country, including San Francisco, have adopted similar measures in the wake of incidents like the one in May when a White woman in New York City’s Central Park called the police on a Black man who was bird watching.

“I feel it’s important. I don’t think people should be afraid to go out and do their own thing, without feeling threatened,” said Jeremiah Zhorne, an 11th grader at Iowa BIG.

Jeremiah said he’s felt unfairly profiled and targeted because he’s Black. And when he’s made mistakes, he feels he was judged more harshly than his White peers.

His classmate Jada Scott, a 12th grader, has had similar experiences. A neighbor repeatedly called the police on her family after they moved to a predominantly White neighborhood, and sometimes police cars would cruise by her house unnecessarily.

“I felt targeted, most definitely degraded, like we weren’t supposed to be there,” she said. “It made me want to do something about it.”

Working with their teacher, Jada, Jeremiah, and a few other classmates researched discriminatory practices and put together a plan. They met with their state representatives, local leaders from the NAACP and other Back organizations, and police and city leaders. They studied data, surveyed people in the community, and found out how to take their idea and turn it into state law.

Their teacher, Becky Herman, said it’s a valuable experience because it’s entirely student-driven. But it’s also allowed the students to feel empowered in a time of great social unrest in the United States.

“I believe we are witnessing a seismic shift in civil rights activism that we haven’t seen since the ‘70s,” she said. “The timing and climate are right for more equity legislation, and I feel this effort is both empowering and engaging for this group of students.”

Amia McCoy, an Iowa BIG 12th grader, said the experience has been interesting and rewarding, and she’s hopeful their idea will lead to real change. It’s long overdue, she said.

“I was tired of waiting for change. I wanted to be the change,” she said. “Why? Because it’s our future.”

Want to hear more about how students are getting involved and shaping the future of our country? See these stories on student activism:

- At Texas Boys State, the Kids, In Fact, Are Not Alright

- #BlackLivesMatter Murals in Downtown Oakland Bring Hope and Inspiration

- Meet the Student Activists Leading the Country’s Protests for #BlackLivesMatter