Living History: Bringing Dr. King & Civil Rights Education to the Classroom

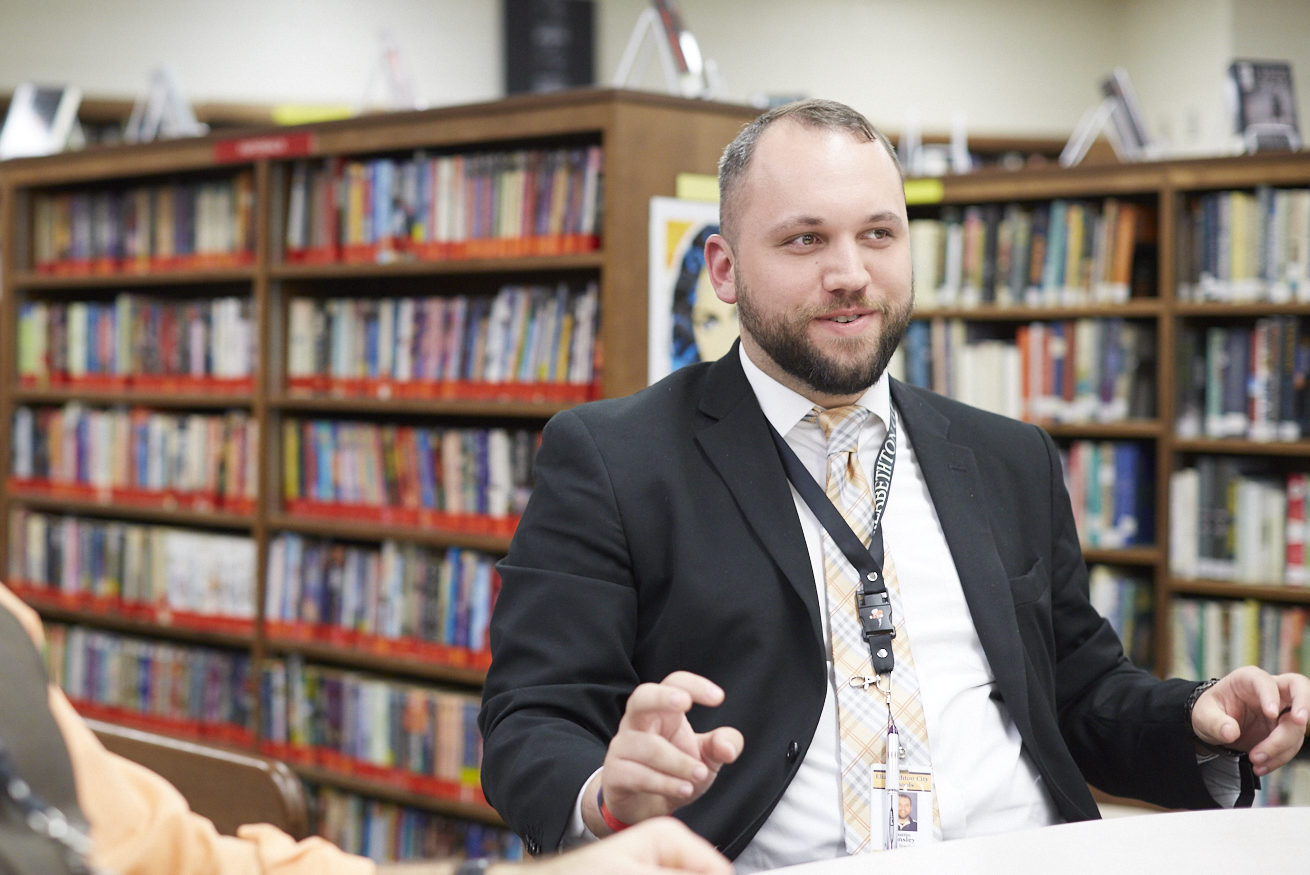

While attending the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) conference in Atlanta, Georgia, in 2016,…

While attending the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) conference in Atlanta, Georgia, in 2016, I had the chance to visit the National Center for Civil and Human Rights with a small cohort of fellow teachers. The entire museum was rewarding, but one exhibit created a transformative experience. It allowed me to understand better the dynamic stories of the Dr. Martin Luther King civil rights movement and those who fought for equality.

At the Lunch Counter Sit-In exhibit, you walk up to a mockup of a polished 1960 whites-only lunch counter with a mirror wall so you can witness yourself and others. The exhibit is an intense recreation of a nonviolent sit-in protest. There’s a timer in front of your seat to track your duration. You’re directed to place your palms on embossed hand prints and to raise your feet onto the stool supports. You put on sound-canceling headphones, close your eyes, and are transported back in time. You’re called names through the whispers and shouts of men, women, and children. The chair and table vibrate as it simulates aggressive patrons hitting the furniture. And then, the moment you stand up, the simulation ends. The timer tells you how long you were sitting. For me, two minutes felt like hours.

I wept. I looked in the mirror at my fellow teachers, and we all shared the same response. Afterward, we talked about how we wished our students could experience all the museum offers. We wondered how we could bring history to life in the classroom in a way that felt as transformative as the sit-in exhibit. Students didn’t need to experience the trauma, but they deserved the same meaningful, engaged learning we had just experienced (it’s one of our research-backed XQ Design Principles to rethink the high school experience, so more students graduate ready for college and careers).

The MLK Day holiday reminded me of this experience because, like many other educators, I have struggled to teach Dr. King’s history during the annual holiday in a meaningful way. With high schoolers, I didn’t want to revisit information they may already know because I feared the lesson wouldn’t feel authentic. But I also wanted to introduce new elements to better contextualize their understanding. What to include and what to omit was a real challenge.

XQ’s Senior Education Editor Beth Fertig heard about this struggle from teachers a decade ago when she was a reporter at WNYC Public Radio. As one teacher told her, Dr. King is a big tree in a forest of advocates. His legacy is dynamic, and we should be immersing students in a richer understanding of the world he and other civil rights activists were experiencing and seeking to change.

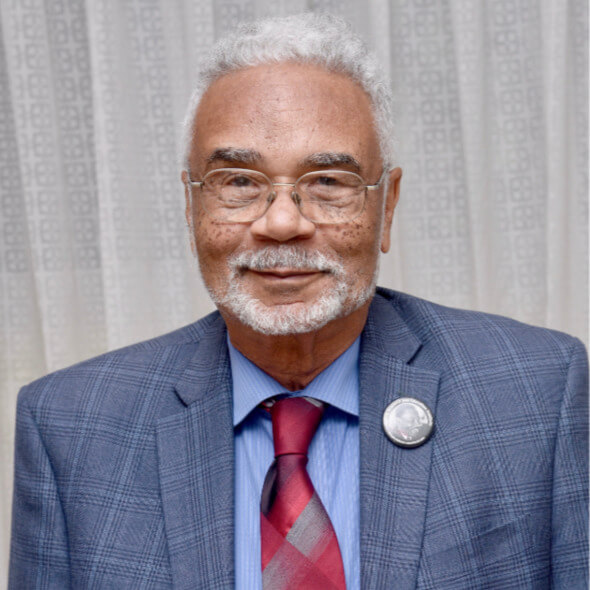

Just before the 2022 Christmas break, I spoke with Dr. Clayborne Carson about how we can improve our teaching about Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement on MLK Day and throughout the year. Carson is the founding director of The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University. He now directs the World House Project (WHP) at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law. We discussed how their contributions can help teachers create a multimedia approach to enhance student learning.

Teaching About Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement

The World House Project creates highly engaging multimedia lesson plans for teachers to use in their classrooms. By using documentaries, images, digital content, and social media posts in tandem, teachers can meet students where they are. This multimedia strategy is part of WHP’s mission to transform their academic research of Dr. King and other civil rights activists into engaging materials for educators. “I’m more concerned about how you get this out to the world—particularly to young people,” Carson explained.

To get teachers started, the World House Project provides course outlines, podcasts, and lesson plans. Those under the Liberation Curriculum ask students to engage with primary materials and learn how they came into existence. The goal is to show that primary materials, like speeches, letters, lectures, and pamphlets, don’t exist in vacuums–that they were created by real people facing real challenges and were consumed by people as real as them.

Carson produced the recent documentary, “When I Get Grown–Reflections of a Freedom Rider,” a short film that shows how the trauma experienced by a young Bernard Lafayette transforms him into a civil rights icon. Narrated by Lafeyette himself, the film’s footage includes a blend of animation, as well as photos and videos from his life. One reason the World House Project produces documentaries is to show the stories of real people rather than tell them. As Carson pointed out, students are more likely to watch something than to read books. Using a multimedia strategy in the classroom ensures we meet students where they are.

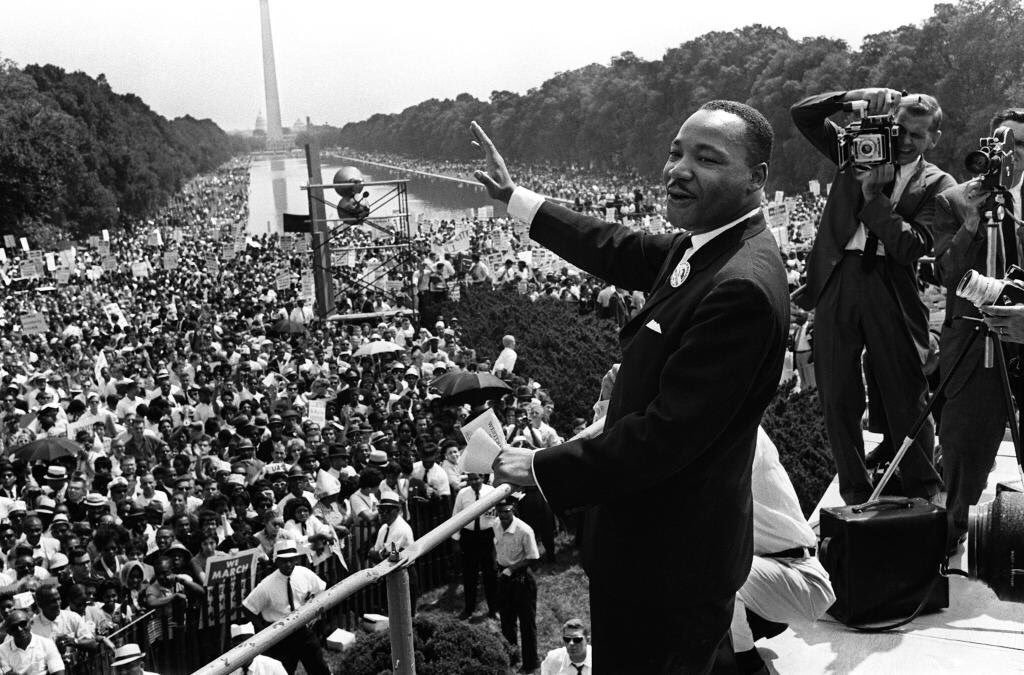

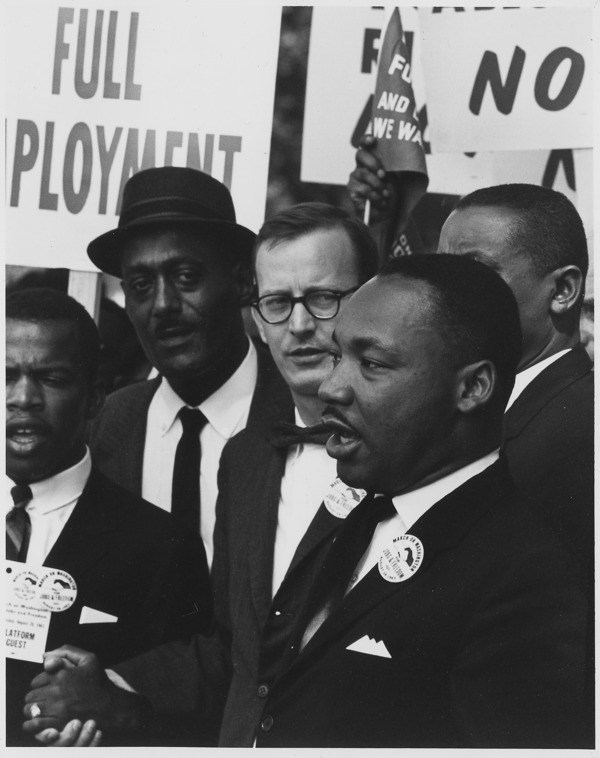

I asked Carson what it was like at the March on Washington in 1963. He painted a vivid picture of witnessing the likes of Dr. King, John Lewis, and so many more who participated in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). His narration reminded me of the interactive sit-in exhibit I experienced at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights while attending the NCTE convention. We talked about how that exhibit simulates the difficult moments of those nonviolent protests.

“History comes alive when you experience it through the eyes of one of the participants—as something you can imagine yourself,” said Carson. For students, it’s not always clear who or what caused such historical moments. “But it didn’t just happen,” he said. “People made it happen.” And students can appreciate that best through more immersive learning.

Carson and I ended our conversation by discussing the pitfalls of teaching history. Too often, it’s presented as: here are the names and dates and what you need to remember, time to move on. But history is a series of choices and consequences. Dr. King, his late wife Coretta, and other activists weren’t always famous. “They were just ordinary people trying to live their lives, who did extraordinary things,” Carson said. “That’s a tremendously important lesson to me about what education should be about.”

When teachers approach the MLK Day holiday and civil rights, we should consider who these historical figures were and what was meaningful to them. These human connections can make the historical world feel real for students. As Carson said, “It should be about widening your vision and liberating yourself to the point where you can imagine something—the best version of yourself and or reimagining what that best version would be. We can transform what education is conceived of when we get to that point.”

Resources for Teachers:

The Liberation Curriculum is a great place for teachers looking to expand the breadth of their lessons about Dr. King and civil rights. The curriculum includes lesson plans, multimedia activities, discussion guides, handouts, and links to primary sources.

Below are two additional resources I’ve used to help enhance multimedia learning in my classrooms:

- Smithsonian Learning Lab. A great resource that allows teachers to discover, create and share interactive multimedia lesson plans that feature Smithsonian artifacts. Lessons and materials can be adapted to meet the needs of your classroom goals.

- PBS Learning Media. If you have a Google Classroom, this database allows you to easily curate a collection of resources to share with your students. It includes lesson plans, activities, and access to beloved PBS content. Many of your students may already be familiar with PBS Digital Studios on YouTube.

Photo at top courtesy of The National Archives Collection, NAID: 237616620